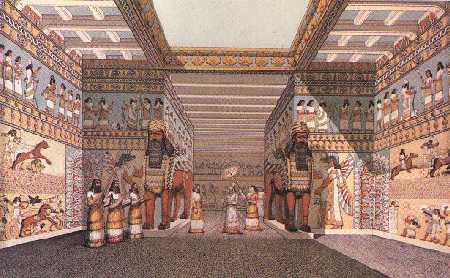

Finally, the action taking place within the

"ceremonial" reliefs exhibit the power and importance of the

king. First off, the panels depicting the deities fertilizing the

sacred tree are important. The sacred tree is shown artistically

in a symmetrical manner with intertwining branches, stylized

leaves, and a fan of leaves above the trunk. The winged geniuses

are fertilizing the sacred tree with a date blossom in their

right hand and holding a sacred bucket in their left. In

addition, panel three shows a winged deity following

Assurnasirpal with his right hand raised over the king "in a

gesture of benediction and divine protection" (Art History

Anthology 28). By placing these reliefs in his antechamber and

living room, Assurnasirpal "emphasizes the sacred character of

the Assyrian king, elected by the gods, although not himself of

divine substance" (Frankfort 87).

In conclusion, we find that the reliefs from the palace of King

Assurnasirpal II play an important role in exhibiting the power

and importance of the king. While an Assyrian king's power can be

depicted is a war-like manner by his military might, we learn

that "ceremonial" reliefs are also effective by placing the king

in relation to gods. The power and importance of the king is

shown through a peaceful manner that highly contrasts the scenes

of death and fighting found in such reliefs as the lion hunt of

Assurbanipal and the battle scene of Assurnasirpal.

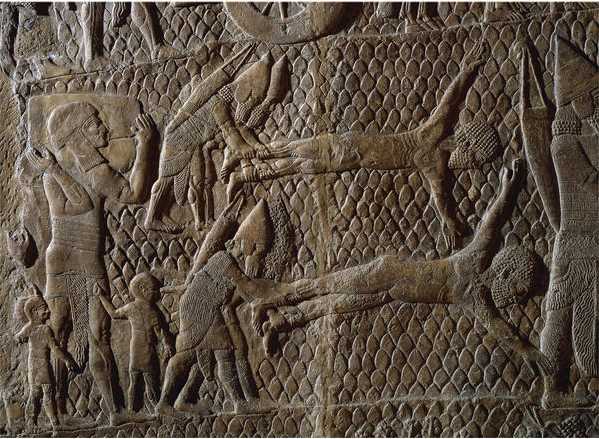

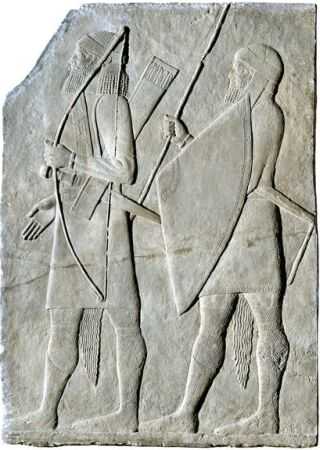

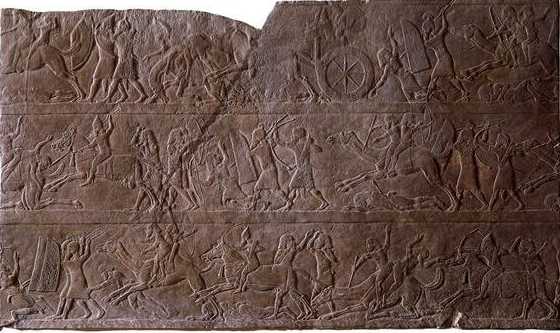

Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), northern Iraq

Neo-Assyrian, about 730-727 BC

Stone panel from the Central Palace of Tiglath-pileser III

A successful Assyrian campaign against the Arabs

This alabaster panel decorated the mud-brick walls of the Central Palace of King

Tiglath-pileser III (reigned 745-727 BC). It is one of a series of panels that

depicts a procession of prisoners and booty captured during one of the king's

campaigns against Arab enemies.

A woman leads a herd of camels. The one-humped camel, or dromedary, was probably

domesticated by the inhabitants of Arabia at the end of the second millennium BC.

Under Tiglath-pileser the administration of defeated territory was reorganized

by extending direct Assyrian rule over them, transforming them into provinces of

an empire. These provinces included territory as far west as Damascus.

Increasingly Assyrian kings came into conflict with Arabs.

The Arabs first appear in Assyrian records in the ninth century BC. Assyrian

texts tell of Arab tribes led by queens, and show how they became increasingly

important for escorting trading caravans or military expeditions in northern Arabia and Sinai.

Height: 99 cm Width: 162 cm

Nineveh [Ninive] (Iraq)

The site of Nineveh lies on the east bank of the

River Tigris. The ancient tell, now known as Tell Kuyunjik, was

occupied from the seventh millennium BC. A deep excavation at the

site, carried out by Max Mallowan, established a chronology

against which many of the other sites in north Mesopotamia are

compared.

In the later second millennium BC, Nineveh was an important city

with a prestigious temple of the goddess Ishtar. Sennacherib

chose it as his capital and laid out a city surrounded by walls

approximately twelve kilometres in circumference. The old tell

formed the main citadel and was where, at the beginning of the

seventh century BC, Sennacherib built the so-called Southwest

Palace, decorating it with carved stone reliefs. As at Nimrud and

Khorsabad, there was also an arsenal. This was situated on the

river wall south of the citadel mound at Tell Nebi Yunus

(so-called because later legend claimed this was the tomb of the

prophet Jonah). Ashurbanipal built a second palace on Tell

Kuyunjik, the North Palace, which contained the famous lion hunt

reliefs. In the summer of 612 BC, Nineveh fell to the combined

forces of the Medes and Babylonians. Occupation continued,

however, for a further 1000 years before Nineveh was eclipsed by

the city of Mosul, on the other side of the river.

Nineveh (Ninive), northern Iraq

Neo-Assyrian, about 700-681 BC

Stone panels from the South-West Palace of

Sennacherib

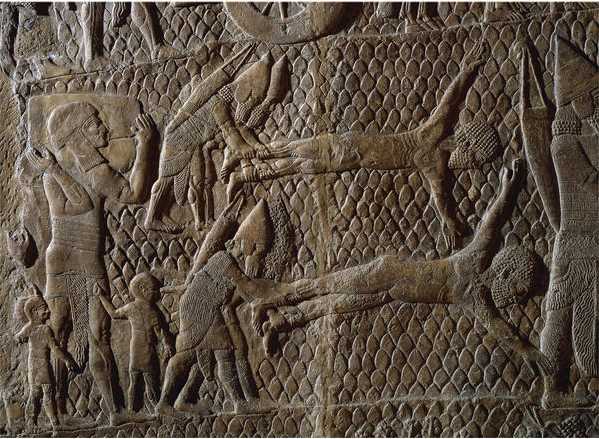

The siege and capture of the city of Lachish, in the kingdom

of Judah, in 701 BC

Length: 172 cm Width: 61 cm

These alabaster panels were part of a series which decorated the

walls of a room in the palace of King Sennacherib (reigned

704-681 BC).

These three surviving slabs complete the royal entourage. The

right-hand end shows more cavalry and chariots waiting behind the

king. It also shows an aerial view of the Assyrian camp with its

oval wall and defensive towers at intervals shown flattened out.

Other Assyrian camps shown on reliefs were sometimes round or

rectangular. The camp seems to have been methodically planned

with a road running through the middle. There are two pavilions,

like the one behind the king, and five open tents in which

various activities can be seen, including the amusing scene of

two men gossiping over a drink. The pair of chariots in one

corner of the camp have a standard in each of them; these are the

chariots of the gods, sometimes seen charging in battle. On this

occasion two priests in tall hats are performing a ceremony; an

incense burner stands higher than the priests, and a sacrificial

leg of meat sits on an altar.

The siege and capture of the city of Lachish in 701 BC

Length: 269 cm Width: 180 cm

Having been exiled from their city, the people of Lachish move through the

countryside to be resettled elsewhere in the Assyrian Empire. Below them high

officials and foreigners are being tortured and executed. It is likely that

they are being flayed alive. The foreigners are possibly officers from Nubia.

The Nubians were seen as sharing responsibility for the rebellion. Much of Egypt

at this time was ruled by a line of kings from Nubia (the Twenty-fifth Dynasty)

who were keen to interfere in the politics of the Levant, to contain the threat

of Assyrian expansion. As Sennacherib's forces laid siege to Lachish, an Egyptian

army appeared, led by a man called Taharqa, according to the Old Testament.

He may be the later pharaoh of Egypt with the same name (690-664 BC).

Sennacherib's account claims that the rebels had called on the support of

the kings of Egypt (Delta princes) and the Kings of Kush (Nubia).

The armies clashed on the plain of Eltekeh. While Sennacherib claimed victory,

he was still not able to capture Jerusalem.

Nineveh, northern Iraq

Neo-Assyrian, about 645 BC

Stone panel from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal

Hunting with hounds

This stone panel decorated a mud brick wall of the palace of

King Ashurbanipal (reigned 669-630 BC) at Nineveh. It was

originally part of a much longer composition relating to the

royal sport of lion hunting. The figures leading the hounds are

hunt attendants.

The use of such mastiffs is well represented on the wall reliefs

at Nineveh. They are used to guard the edge of an arena in which

the king kills lions and, in a separate hunting composition, they

are used to bring down wild asses. Scenes of hunting are a common

motif in Mesopotamian art reflecting the king's conquest of

chaotic and dangerous nature.

Dogs may have been the earliest animals to be domesticated by

humans, perhaps by 10,000 BC or earlier. In Mesopotamia some of

the earliest evidence for the presence of dogs comes in the form

of skeletons found in the graves at Eridu in the south and dating

to around 5000 BC. They have been identified as greyhounds.

It has been suggested that the disease of rabies was present in

Mesopotamia by the beginning of the second millennium BC and

representations of dogs, possibly for magic protection, make

their appearance.

The Mesopotamians considered the dog family to include not only

domestic dogs, wolves, hyenas and jackals, but also lions.

Height: 107 cm (approx.)

Width: 102cm (approx.)

Depth: 18cm (approx.)

Nineveh, northern Iraq

Neo-Assyrian, around 645 BC

The Dying Lion, a stone panel from the North Palace of

Ashurbanipal

The triumph of the Assyrian king over nature

This small alabaster panel was part of a series of wall panels

that showed a royal hunt. It has long been acclaimed as a

masterpiece; the skill of the Assyrian artist in the observation

and realistic portrayal of the animal is clear.

Struck by one of the king's arrows, blood gushes from the lion's

mouth. Veins stand out on its face. From a modern viewpoint, it

is tempting to think that the artist sympathized with the dying

animal. However, lions were regarded as symbolizing everything

that was hostile to urban civilization and it is more probable

that the viewer was meant to laugh, not cry.

There was a very long tradition of royal lion hunts in

Mesopotamia, with similar scenes known from the late fourth

millennium BC. The connection between kingship and lions was

probably brought to western Europe as a result of the crusades in

the twelfth and thirteenth centuries AD, when lions begin to

decorate royal coats of arms.

Height: 16.5 cm

Width: 30 cm

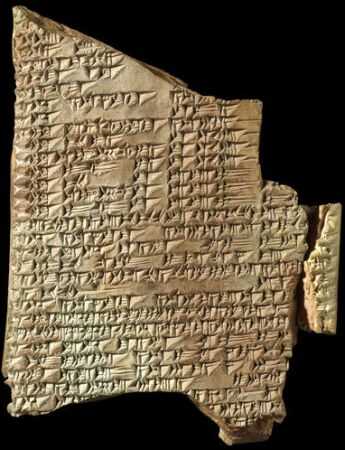

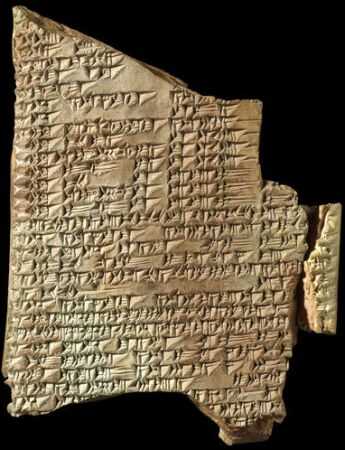

Neo-Assyrian, 7th century BC

From Nineveh, northern Iraq

Tablet telling the legend of Etana

Part of the library of King Ashurbanipal (reigned 669-631

BC)

The story told on this tablet centres on Etana, a legendary king

of the southern Mesopotamian city of Kish.

An eagle has its nest in the branches of a tree while a snake

nests at its base. The two animals swear an oath of friendship by

Shamash, god of the sun and justice. They both raise their young,

but the eagle eats the young snakes. The snake cries to Shamash

who tells it to hide in the carcass of a dead wild bull. The

eagle flies down to eat from the bull, but is seized by the

snake, who ties its wings and throws it into a pit.

Meanwhile, Etana, a pious man, prays to Shamash for a son and

the plant of life. Shamash tells Etana where to find the eagle,

so that it can help him to find the plant. For seven months Etana

teaches the eagle how to fly again. But the eagle is unable to

find the plant, and suggests that they fly up to heaven to speak

with the goddess Ishtar. Etana is frightened by the height they

fly and they have to make several attempts at the journey.

We do not know whether they were successful, as unfortunately

the rest of the text is missing and the end of the story is

unclear. Versions of the legend are known from as early as the

seventeenth century BC, but the story is certainly much

older.

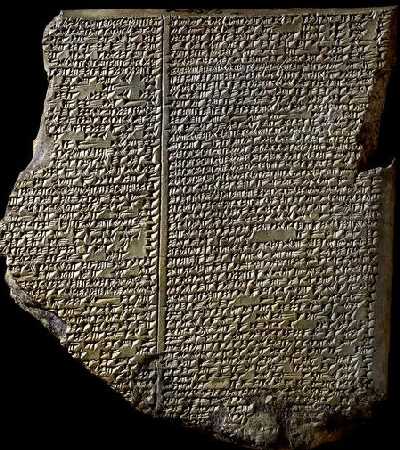

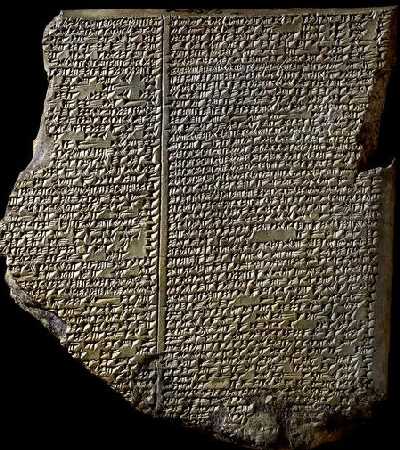

Neo-Assyrian, 7th century BC

From Nineveh, northern Iraq

The Flood Tablet, relating part of the Epic of

Gilgamesh

The most famous cuneiform tablet from Mesopotamia

The Assyrian King Ashurbanipal (reigned 669-631 BC) collected a

library of thousands of cuneiform tablets in his palace at

Nineveh. They recorded myths, legends and scientific information.

Among them was the story of the adventures of Gilgamesh, a

legendary ruler of Uruk, and his search for immortality. The Epic

of Gilgamesh is a huge work, the longest literary work in

Akkadian (the language of Babylonia and Assyria). It was widely

known, with versions also found at Hattusas, capital of the

Hittites, and Megiddo in the Levant.

This, the eleventh tablet of the epic, describes the meeting of

Gilgamesh with Utnapishtim. Like Noah in the Hebrew Bible,

Utnapishtim had been forewarned of a plan by the gods to send a

great flood. He built a boat and loaded it with everything he

could find. Utnapishtim survived the flood for six days while

mankind was destroyed, before landing on a mountain called

Nimush. He released a dove and a swallow but they did not find

dry land to rest on, and returned. Finally a raven that he

released did not return, showing that the waters must have

receded.

This Assyrian version of the Old Testament flood story was

identified in 1872 by George Smith, an assistant in The British

Museum. On reading the text he

" ... jumped up and rushed about the room in a great state of

excitement, and, to the astonishment of those present, began to

undress himself."

Length: 15 cm

Width: 13 cm

Thickness: 3 cm

|

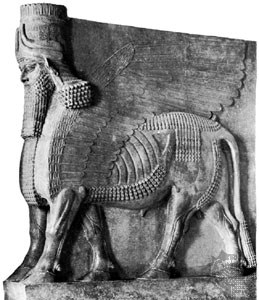

"In this magnificent edifice I had opened no less than

twenty-one halls, chambers, and passages, whose walls, almost

without exception, had been paneled with slabs of sculptured

alabaster recording the wars, the triumphs, and the great deeds

of the Assyrian King (Sennacherib). By rough calculation, about

9880 feet, or nearly two miles, of bas- reliefs, with

twenty-seven portals, formed by colossal winged bulls and lion

sphinxes were uncovered" (TCOLBS 66)

"In this magnificent edifice I had opened no less than

twenty-one halls, chambers, and passages, whose walls, almost

without exception, had been paneled with slabs of sculptured

alabaster recording the wars, the triumphs, and the great deeds

of the Assyrian King (Sennacherib). By rough calculation, about

9880 feet, or nearly two miles, of bas- reliefs, with

twenty-seven portals, formed by colossal winged bulls and lion

sphinxes were uncovered" (TCOLBS 66) In the 1st slab many

different types of archers and slingers are depicted, as the

Assyrian army was made up of many different ethnic groups pressed

into service this is possible. The archaeological evidence at the

site that supports the idea of many different groups, as depicted

in the reliefs is they fact that as many as 30 different styles

of arrow heads are found stuck into the destruction rubble at

level 3 of the tell. (BASOR) Most of the arrow heads are Iron,

but copper and even bone arrowheads are mixed into the bunch. The

bone arrowheads are probably just a contaminate to the

record.

In the 1st slab many

different types of archers and slingers are depicted, as the

Assyrian army was made up of many different ethnic groups pressed

into service this is possible. The archaeological evidence at the

site that supports the idea of many different groups, as depicted

in the reliefs is they fact that as many as 30 different styles

of arrow heads are found stuck into the destruction rubble at

level 3 of the tell. (BASOR) Most of the arrow heads are Iron,

but copper and even bone arrowheads are mixed into the bunch. The

bone arrowheads are probably just a contaminate to the

record.