| by Anna

Blennow (University of Göteborg).

The church San Lorenzo in Lucina,

like many other churches and buildings

in Rome, has a collection of elder

inscriptions, most of them attached to

the walls of the portico.

A number of early christian inscriptions

were found during an excavation

beneath palazzo Fiano, in close

vicinity to the church, in 1872. They

belonged to a tomb-area from the

8th century, and have probably

been brought to the church frome

some abandoned catacomb to serve

as building materials, as was usual

at that time. Also medieval material was

found. Most important were the fragments

of an epitaph for a certain deacon

named Paulus. It is dated to 783,

the time of pope Hadrian I, during which a

large number of churches in Rome

were restored, including San Lorenzo in Lucina.

The damage to the material may have

been a result of later plundering, most

probable in 1084, when Robert Guiscard

with his Norman soldiers sacked Rome

for three days, and the region of

the church was almost completely destroyed.

Below, each inscription has a number

preceded by a letter indicating W(est),

E(ast) or S(outh) wall of the portico.

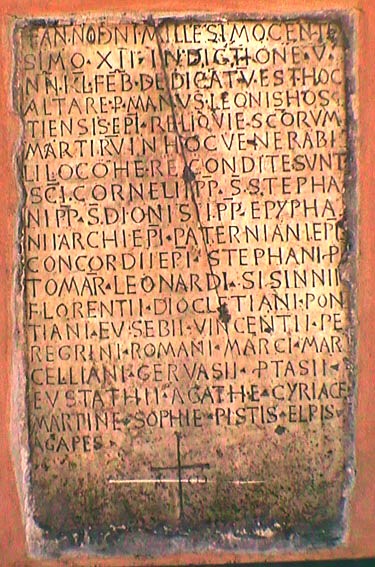

The early christian inscriptions

W2.

Text:

Hic iacet Rigina qu<a>e vixit

annus pl(us) m(inus) XVII d(e)p(osita)

XVII kal(endas) oct(obres)

Translation: ”Here lies Regina, who

lived more or less for seventeen years and

was buried seventeen days before the kalendae of October (the 15th of september).”

The narrow letter-proportions and

the thin lines without modulation are

typical for early christian inscriptions.

The crux monogrammatica in the

upper line and the formula hic

iacet date the inscription to the 4th or 5th

century. (ICUR I, 428; ILCV

3060; de Rossi 1872–73, 51) |

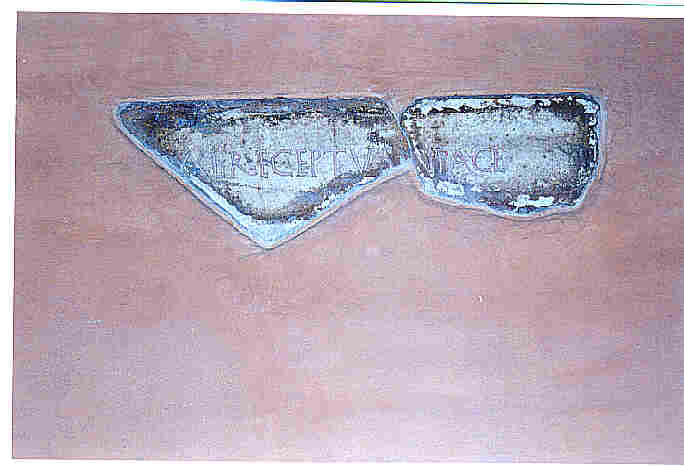

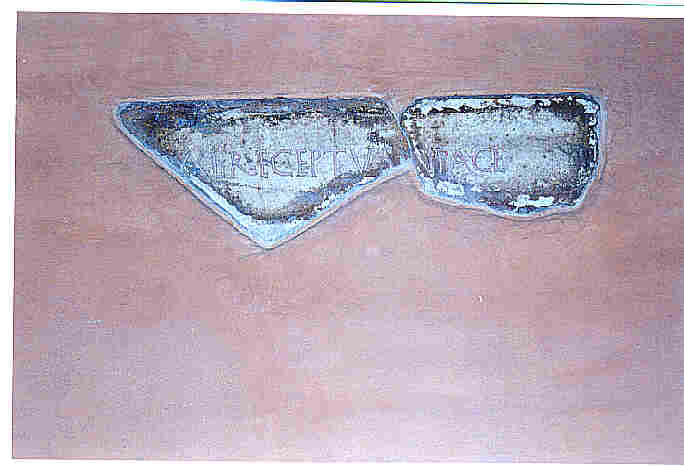

S5 (photo, see S7 below).

Text:

LUS Qui vixit

[l]EOnis de[p]

Translation: ”...lus who lived ...

buried [during the consulate of] Leo”

(late 5th century)

The letters are irregular with no

line-modulation and inconsistently used serifs.

X has the typical emphasis on the diagonals, which is common in

inscriptions of late antiquity. ”The

consulate of Leo” would date the inscription

to 458, 474 or 475. (ICUR I, 423; de Rossi 1872–73, 49) |

S6.

Text:

[---] nus XXII receptus in pace

[---] s

Translation: ”... twenty-two years,

received in peace ...”

The letter-proportions are close

to the Roman capitalis quadrata, and the formula receptus in

pace dates the inscription to the 3rd or 4th century. (ICUR

I, 429; ILCV

2922, de Rossi 1872–73, 49) |

S7.

Text:

[---] opra [---] resb [---]

This fragment originates from an

inscription of pope Damasus (366–384). He was the author of several inscriptions

in verse about martyrs. The designer of the very beautiful letter-forms

was the pope's friend Furius Dionysius Filocalus. The

distinct character of the letters – a remarkable contrast between thick

and thin strokes, the stem ending in

a drop-shape, and thin, curled, elegant serifs – makes it possible to distinguish

the filocalian letter from imitations

and thus confirm the origin of an inscription even in a very

small fragment like this. (ICUR

I, 425; de Rossi 1872–73, 52; Ihm 1895, 54; ED 56) |

All the inscriptions above are preserved

in the portico.

The Paulus-inscription

parce praecor Paulo sanct[oru]m maxim[e

praesul]

alta patere poli fac illi culmina

Chr[iste]

vivat in aeterio felix per secla

[senatu]

luce fruatur ovans [re]gno laetetur

O[lympi]

vita sequatur eum mortis sic

vincula vincat

semper in aeterna caelesti floreat

aula

pauso sepultus ego Paulus praesentib(us)

exul

dep(ositus) id(ibus) mart(iis)

ind(ictione) VI temp(ore) d(omini) n(ostri)

Hadriani papae

”Have mercy upon Paulus, I beg, o

foremost of the hallowed;

Open the heights of the sky for

him, o Christ;

May he live fortunate through the

centuries in the ethereal senate;

May he enjoy the light, exultant,

and rejoice in the kingdom of the Olymp;

May life follow him, and so may

he conquer the chains of death;

May he always flower in the eternal

palace of heaven.

Here I, Paulus, lie buried, an exile

from the present.

Buried on the Idus (the 15th) of

March, in the 6th indiction, in the time of our

lord pope Hadrianus.”

The inscription is hexametrical,

and the letter-forms are well-executed for the

late 8th century. The acrostics (the first and last letters of each

line, read from top to bottom) read

Paulus Levita (deacon). The inscription is

fixed to the wall to the right of the entrance to the Scavi. (ICUR

I, XIV, 2; de Rossi 1872–73, 42) |

The 12th century inscriptions

Five inscriptions from the 12th century

are preserved in the church. They

all relate to the eventfulness of

this period, including restorations after

the Norman sack in 1084; consecrations

and reconsecrations of the church,

new altars and an extensive collection

of relics. Four of them are situated

in the portico, and the fifth is

found on the cathedra hidden by the 17th

century wooden panel behind the

altar.

(Silvagni 1943, XXII, 2–3; XXIII,

2,6; XXVI, 4)

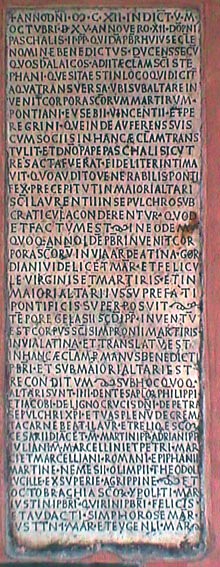

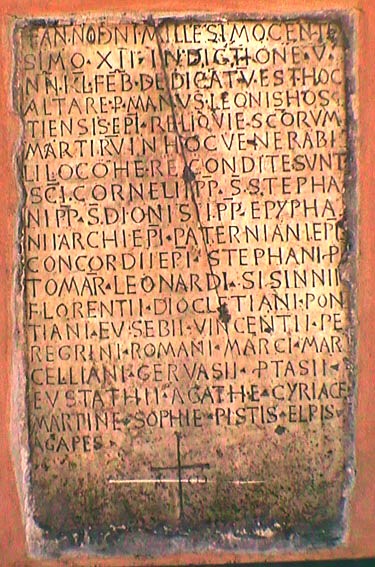

S10 Inscription

S10 describes how Leo, bishop of Ostia, consecrates an altar in S. Lorenzo

in Lucina on January the 24th, 1112; and a list is added of relics

deposited in it. The cathedra inscription also mentions this consecration,

but adds that the grid-iron of St. Laurentius and two vessels

filled with his blood were taken out

from the old altar by pope Paschal II,

and that the relics were viewed

for several days by the Roman people before bishop Leo’s consecration on

January the 24th. A mysterious time-error occurs in the inscription, namely

the date of 27th of January for pope Paschal’s action, which of course

can’t have occured after the consecration of the new altar. |

|

|

|

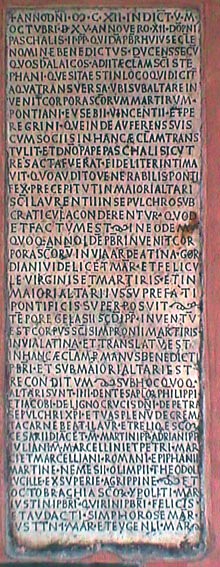

Inscription no. S4

tells about a certain presbyter called Benedictus,

collecting relics of martyrs to the

church between the years 1112–1119, and the relics are put in the high

altar under the grid-iron of St. Laurentius. Then follows a long list of

other relics deposited in this place, among them a vessel filled with burnt

flesh of St. Laurentius. |

|

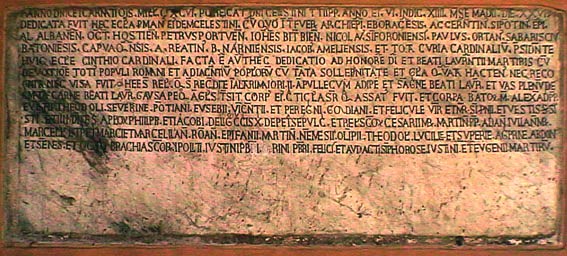

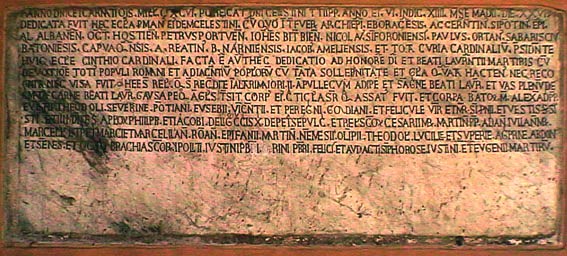

| Inscription no. S9

describes the antipope Anacletus II consecrating the whole church in 1130,

perhaps when the restorations, started under pope Paschal II, were completed. |

|

|

The Lateran council of 1139, however,

cancelled all actions performed by the antipope, and a new consecration

was needed. This was made as late as 1196 by pope Celestinus III, an event

which is recorded in inscription no. S3.

|

| Bibliography

Ihm 1895

Anthologiae Latinae Supplementa:

Damasi epigrammata, ed. M. Ihm, Leipzig 1895.

ED

Epigrammata Damasiana, ed.

Ferrua, A., Città del Vaticano 1942.

ICUR

Inscriptiones Christianae Urbis

Romae I, ed. Silvagni, Roma 1922.

ILCV

Inscriptiones Latinae Christianae

Veteres, ed. E. Diehl, Berlin 1961.

Silvagni 1943

Monumenta epigraphica Christiana

saeculo XIII antiquiora, ed. A. Silvagni, Città del Vaticano

1943.

de Rossi 1872–73

de Rossi, G. B., ”Sepolcri del secolo

ottavo scoperti presso la chiesa di S. Lorenzo in Lucina”, Bullettino

della commissione archeologia municipale, 1872–73, pp. 42–53. |

|