|

Sulle tracce della tessitura a "liccetti"

Itinerario storico – turistico

On the tracks of weaving by "liccetti"

Historical - touristic itinerary

|

|

|

|

|

SI RINGRAZIA: THANKSTO: Provincia di Macerata Dott.ssa Silvia Bernardini - Assessore Attività Produttive Dott.ssa Letizia Casonato - Dirigente Rag. Rosella Pagnanelli Comune di Camerino Comune di Pievebovigliana Prof. Giorgio Quintili - Direttore Pinacoteca Parrocchiale Don Cherubino Ferretti - Direttore Museo Diocesano Don Piero Allegrini - Direttore Museo Piersanti Dott. Fernando Mattioni - Direttore Museo della Nostra Terra Don Mario Scuppa Mons. Pietro Paolo Ferretti Don Franco Gregori Ing. Girolamo Maraviglia Parroci di Belforte, S. Severino Marche, Cingoli, Tolentino e quanti hanno contribuito alla realizzazione di tale pubblicazione TESTI Patrizia Ginesi - Maria Giovanna Varagona TRADUZIONE Maria Carpino FOTO Massimo Costantini PROGETTO GRAFICO Marika Mariani - Massimo Costantini - Patrizia Ginesi TIPOGRAFIA La Nuova Stampa 2006

|

PRESENTAZIONE La presente pubblicazione nasce dalla volontà di far riscoprire ed apprezzare i valori autentici di cui è ricca la nostra civiltà e di rivalutare le peculiari tradizioni maceratesi radicate nel tempo e nella storia. La tessitura manuale eseguita secondo l'antica e complessa tecnica dei “liccetti”, rappresenta una preziosa arte fin dai tempi remoti ed esprime l'ingegno, l'originalità e la creatività dei nostri progenitori, che l'hanno sapientemente saputa custodire e tramandare. Oggi, vivendo nella realtà della comunicazione globalizzata contemporanea, comprendiamo che per partecipare alle sfide più importanti nei settori artistico, culturale, nonché economico e sociale, occorre differenziarsi qualitativamente. Il valore aggiunto sarà rappresentato proprio dal confronto dei valori della storia di un territorio, in mancanza del quale si determinerebbe la sconfitta del modello proposto. Il nostro patrimonio storico-tradizionale è indiscutibilmente ricco di autentiche eccellenze culturali, artigianali, naturalistiche ed agroalimentari e, grazie alla saggezza, alla laboriosità ed al buon senso della nostra gente è rimasto inalterato nel tempo, può riuscire ad esprimere una formula vincente, nella realizzazione del prodigioso equilibrio tra progresso tecnologico e rispetto per la tradizione. Da qui l'importanza fondamentale di ricostruire la nostra identità territoriale, facendo leva sui suoi caratteri distintivi, per migliorare lo sviluppo locale integrato e sostenibile e la competitività della provincia e per recuperare, oggi, nei confronti dello scenario mondiale, quella prestigiosa centralità vissuta in passato, in Italia e in Europa.

The present publication arises from the desire to encourage the rediscovery and appreciation of the authentic values which our civilization is rich of and to revalue the peculiar “maceratesi” traditions deeply rooted in lime and in history. Hand-weaving achieved according to the antique and complex technique of “liccetti”, represents a precious art going back to distant times and expresses the talent, originality and creativity of our ancestors, that have wisely been able to preserve and transmit it. Today, living in the reality of globalized communication, we understand that to be able to participate in the most important challenges in the artistic, cultural, as well as economical and social sectors, it is necessary to differentiate ourselves in the quality. The added value will be represented exactly from the confrontation of the values of the history of a territory, in the absence of which would determine the defeat of the proposed model. Our historical and traditional patrimony is unquestionably rich in authentic cultural, naturalistic and agricultural excellencies and, thanks to the wisdom, laboriousness and good sense of our people has remained unaltered in lime and is capable of expressing a winning formula, in the realization of the prodigious balance between technological progress and respect for tradition. From here the fundamental importance to reconstruct our territorial identity, underlining its distinctive characteristics, to improve its local development integrated and sustainable and the competitiveness of the province and to recover, today, in front of the world-wide scenario, that prestigious "central position" lived in the past, in Italy and in Europe. L'Assessore alle Attività Produttive II Presidente Silvia Bernardini Giulio Silenzi

|

|

|

|

|

A tutti coloro che con le proprie mani e creatività preservano tanta parte del patrimonio culturale.

|

Indice generale Generai index Presentazione .................................................................................... 3 Presentation ...................................................................................... 3 Introduzione ...................................................................................... 7 Introduction ....................................................................................... 7 Sulle tracce della tessitura a "liccetti" ................................................. 11 On the tracks ofweaving by "liccetti" ................................................. 11 Itinerario storico – turistico ............................................................... 42 historical - touristic itinerari ............................................................... 42 Opere pittoriche .............................................................................. 43 Pictorial works ................................................................................ 43 Reperti tessili .................................................................................... 49 Textile remains ................................................................................. 49 Laboratori tessili ............................................................................... 55 Textile workshops ............................................................................ 55 Bibliografia ....................................................................................... 56 Bibliography ..................................................................................... 56

|

|

INTRODUZIONE La tessitura è la prima attività complessa (cum-plectere, intrecciare insieme) attraverso la quale l'uomo interagendo con l’ambiente e le sue risorse si è evoluto, conferendo dignità al proprio aspetto e alla propria vita di relazioni. Più di 12.000 anni fa, intrecciava fibre per fame cesti, giacigli, zattere e capanne e poi abiti vestendo di intrecci vegetali. Da allora l’uomo ha modificato e perfezionato tecniche, strumenti e attrezzature ma, l'uso e la vocazione comunicativa del tessuto è rimasta sempre la stessa: mostrare lo status sociale e l'espressione artistica. A partire dallo studio dei tessuti è possibile arrivare ad una comprensione più equilibrata delle diverse culture, per comprenderne i legami e le influenze che, per secoli in tutto il mondo hanno fatto dei tessuti una merce globale. Tra i mezzi d'espressione, il tessuto è quello che più di tutti ha tratto vantaggio dagli spazi di libertà che si aprono tra pratiche consolidate e sperimentazione, tra pubblico e privato, tra tradizione e rinnovamento, bellezza e utilità. Specialmente nell’ultimo secolo, a volte si è voluto rendere un omaggio formale a molti artigiani e produttori di tessuti definendoli “artisti”, mettendo in risalto il difficile rapporto tra belle arti e arti applicate: tutt’oggi irrisolto. La stessa legislatura parla infatti di artigianato artistico, di tradizione o di qualità, conferendo un plus valore all’artigianato, ma il legislatore non si è ancora pronunciato nello specifico, sui parametri che ne caratterizzano ciascuna area di artigianato, in quanto tema particolarmente complesso e intricato. La passione per l'artigianato o la manualità, l'esigenza di costruire con le proprie mani, come ogni forma di “trasporto emozionale” non

|

INTRODUCTION Weaving is the first complex activity (cum-plectere, to interlace together) through which man interacting with the environment and its resources evolved, conferring dignity to his appearance and to his social life. More than 12,000 years ago, fibres were interlaced to make baskets, pallets, raft and huts as well as clothing dressing whit vegetal interlacements. Since then, man has modified and perfected techniques, instruments and equipment but, the use and the communicative vocation of fabric has always remained the same: to demonstrate social status and artistic expression. Beginning with the study of woven fabrics, it is possible to arrive at a more balanced understanding of the different cultures, to understand the bonds and influences that. for centuries worldwide have made of woven fabrics a global merchandise. Among the methods of expression, woven fabric is what has profited most from the spaces of liberty found between proven practices and experimentation, between public and private, between and renewal, beauty and utility. Especially in the last century, at times there has been a desire to pay formal homage to many artisans and producers of woven fabrics defining them “artists”, emphasizing the difficult relationship between fine arts and applied arts: all of which is still today unresolved. The same legislation in factspeaks of artistic craftsmanship, of tradition or of quality, conferring a higher value to craftsmanship, but the legislator has not yet pronounced himself concretely, regarding the vestments which characterize every area of craftsmanship, in as much as the subject is particularly complex and intricate.

|

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

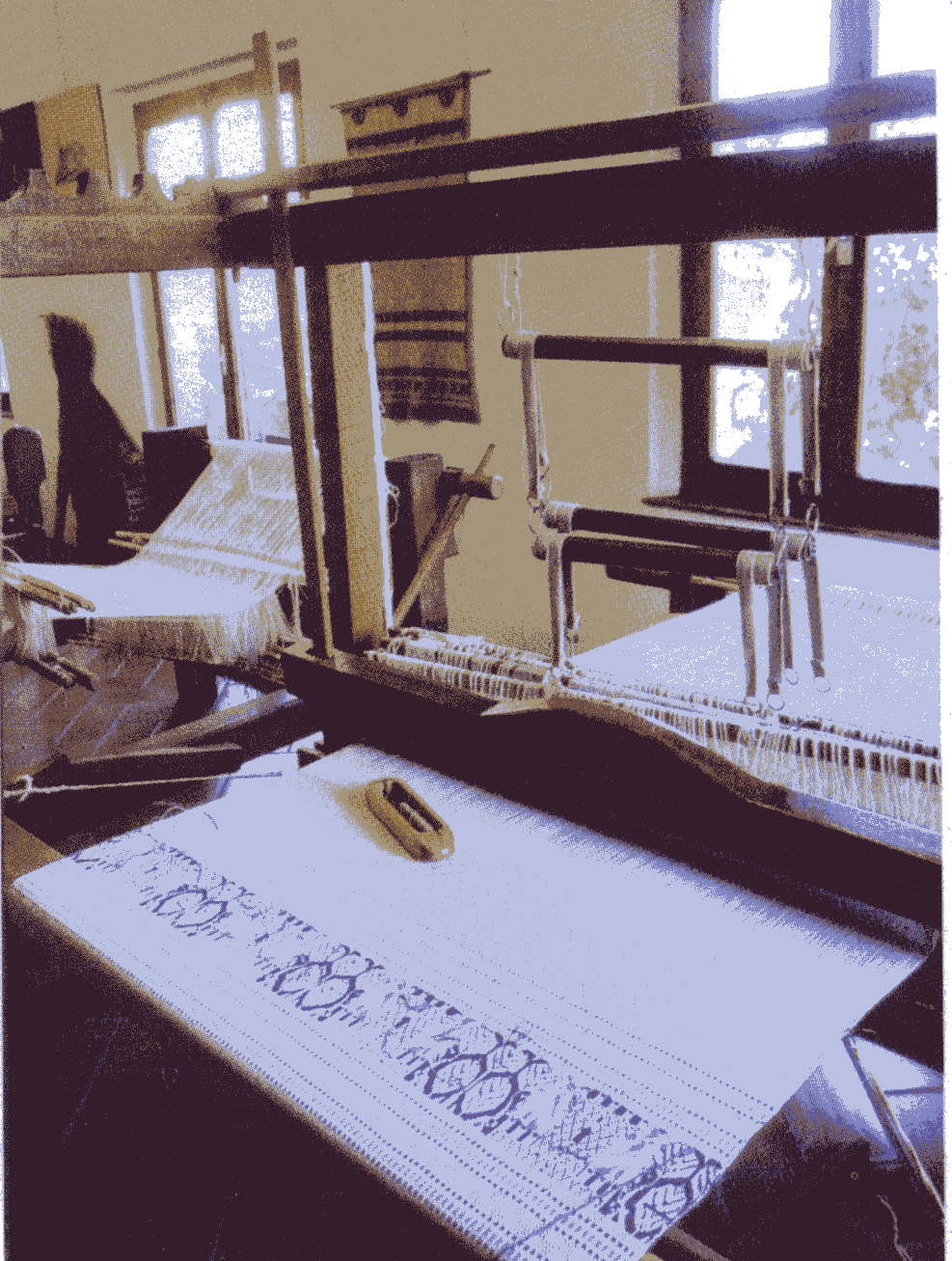

si spiega con la ragione o con le parole; è una necessità espressiva che “colpisce” coloro che vogliono ricercare nella propria interiorità un linguaggio diverso per comunicare parte di se stessi. L'artigianato è fatto di uomini e donne che con la propria capacità creativa e imprenditoriale hanno saputo costruire ricchezza economica e culturale, lasciando tracce che ne hanno valorizzato il patrimonio artistico. Dai secoli passati questi “segni” sono parte della nostra storia, ma il rischio attuale è quello di perdere certe competenze, determinate “sapienze”, abbandonate o sottovalutate in nome dell'innovazione industriale perché ritenute antiproduttive o arcaiche. Come tessitrici e come imprenditrici artigiane, da venti anni insieme nel laboratorio “la Tela”, fin da subito siamo state consapevoli di essere tra le ultime eredi di un patrimonio culturale oramai disperso e dimenticato, da valorizzare sia con il nostro lavoro tessile e produttivo, che attraverso una seria operazione culturale, didattica e divulgativa nei confronti di una tecnica tessile, come quella dei “liccetti”, troppo spesso trascurata da storici o studiosi d'artigianato e ancor più dagli amministratori locali. Le “tovagliette”, motivo di studio di tale pubblicazione, ci colpiscono soprattutto per i bordi decorati con figurazioni vegetali e animaliere, gli stessi ornamenti che caratterizzavano i tessuti serici, della produzione d'arte, prodotti, lungo un arco di nove secoli, dalle famose manifatture della Sicilia, di Venezia, Genova, Lucca e Firenze; furono largamente diffuse in Umbria come nelle Marche ma comunemente vengono definite tessuto umbro. Tenteremo quindi di spiegare come la mancanza di informazione |

The passion far craftsmanship or hand workmanship, the necessity to construct with one’s own hands, like every form of “emotional transport” cannot be explained with words or reason; it is an expressive necessity that “touches” those who want to seek within themselves a different language to communicate a part of themselves. Craftsmanship is made up of men and women that with their own creative and entrepreneurial capability have known how to construct economic and cultural wealth, leaving tracks that have given value to the artistic heritage. Since centuries passed these “signs” are part of our history, but the present risk is that of losing certain competencies, considered “wisdom” abandoned or undervalued in the name of industrial innovation for being considered anti-productive or archaic. As weavers and artisan entrepreneurs, for twenty years together in “la Tela” workshop, since the beginning we have been aware of being among the last heirs of a cultural patrimony at this point lost and forgotten, to valorise with both our textile production, as well as through a serious cultural, didactic and promotional enterprise with regards to a weaving technique, like that of “liccetti”, too often overlooked by historians or scholars of craftsmanship and even more by the local administrators.

The “tovagliette” (small

tablecloths), motive of study for this publication, impress us

above-all for the decorative borders with vegetal and

animalistic figurations, the same ornaments that characterized

silk fabrics, in the production of art,

produced, in the span of

nine centuries, from the famous handmade products

of Sicily, to Venezia,

Genova, Lucca and Firenze; they were extensively spread

out in Umbria as well as in

the Marche but are commonly defined as |

|

|

|

|

8

|

|

|

sul significato storico ed artistico di quei tessuti o del valore culturale dell'opera di ricerca, sia stata la causa del declino consapevole di tanta produzione tessile locale. Inspiegabile indifferenza da parte di studiosi locali, in quanto attualmente è la nostra regione l'unica a detenere il primato riguardo alla produzion e conservazione dell'antica tecnica tessile, che qui denominiamo a “liccetti” nella speranza di sgombrare ogni equivoco sulla sua origine. Il tentativo è quello di dimostrare che, seppure incerta o difficile da confermare risulti la paternità di tale tipologia tessile (esercitata di sicuro anche nelle altre regioni italiane), documenti d'archivio e testimonianze pittoriche, ne confermano la pratica e la produzione tessile nelle Marche, dove a tutt’oggi, nella provincia di Macerata, si trovano solitarie artigiane oppure “hobbiste” in grado di eseguirla. Ciò che ci appare incomprensibile è capire perché un'attività tessile, che ha saputo creare nel passato una forte economia e che ha elaborato sistemi produttivi all'avanguardia nel settore, sia decaduta precipitosamente ogni qualvolta “qualcuno” l'abbia fatta affiorare dall'oblio. Anche se sappiamo che senza una precisa volontà di “rinascita”, attraverso un preciso progetto politico che si traduca in una seria operazione di formazione professionale, culturale e promozionale, difficilmente si possono ottenere risultati duraturi.

Obiettivo primario di questo volumetto è quello di far comprendere l’importanza storica di un artigianato di forte tradizione artistica: la “tovaglietta”, unendo alla ricerca del passato anche un itinerario turistico della nostra provincia sulle tracce di antichi prodotti tessili; un percorso sui luoghi del tessere e non solo, per |

“tessuto umbro” (woven fabric from Umbria). We will attempt to explain how the absence of information on the historical and artistic significance of these woven fabrics or of the cultural value of the work of research, was the cause of the conscious decline of much of the local textile production. Unexplainable indifference, on the part of local scholars, in as a much as our region is presently the only one that has primacy in the production and conservation of the antique weaving, technique, that here we name “a liccetti” in the hope of eliminating any misunderstating on its origin. The attempt is to demonstrate that, even if uncertain or difficult to confirm, the paternity is apparent for this type of textile (practised certainly even in other Italian regions); archive documents and pictorial testimonies, confirm the practice and weaving production in the Marche, where even up to today in the province of Macerata, can be found single artisans or “hobbyists” capable of carrying it out. That which appears to us incomprehensible is understanding why a textile activity, that was able to create in the past a strong economy and that elaborated productive systems that kept up with the times in this sector, look a downfall every time “someone” was able to make it re-blossom from nowhere. Even if we know that without a precise will of “rebirth”, through a precise political project that translates in a serious operation of professional, cultural and promotional formation, it would be difficult to obtain lasting results. The primary objective, of this small volume is to transmit the historical importance of a craftsmanship of strong artistic tradition: the “tovaglietta”, uniting to past research even a touristic itinerary of our "provincia " (defined territory), on the tracks of antique textile |

|

9 |

|

|

ritrovare nelle opere pittoriche o nei sempre più rari reperti tessili, conservati in musei o collezioni, in raccolte pubbliche e private, nelle chiese parrocchiali, i “segni” delle nostre radici. Crediamo e speriamo che non sia troppo tardi salvaguardare un patrimonio quasi totalmente estinto e che non sia troppo tardi riappropiarsene, per parlarne in maniera costruttiva e propositiva. E' nata quindi da questa analisi l'esigenza di un breve scritto che si è potuto materializzare grazie alla particolare sensibilità dell'attuale Amministrazione Provinciale, nella persona dell'Asses-sore alle Attività Produttive Dott.ssa Silvia Bernardini. Ciò ci fa sperare che, insieme al riconoscimento storico, all'obbligo istituzionale, si maturi un progetto chiaro per la promozione dell'artigianato artistico, che oggi può trovare altre committenze per la sua diffusione, per convertirsi soprattutto in occasione di lavoro. Da qui, l'idea che non si può pensare ad un tessuto politico e democratico aperto ad uno sviluppo socio-economico del territorio senza avere la capacità di “ordire” i diversi elementi che lo caratterizzano, con la stessa cura del tessitore quando si dispone alla preparazione del suo ordito. Avere cura significa prestare attenzione ad ogni filo che compone l'ordito, per estensione conoscere e avere cura di ogni parte dei vari settori di sviluppo di un'economia: artigianato, agricoltura, turismo, per lanciare “trame” significative che abbiano l'obiettivo di “tessere” lo sviluppo del territorio. Patrizia Ginesi |

products, a journey to the places of weaving and not only, to rediscover in the pictorial works or in the always rarer woven textile remains, conserved in museums or collections both public and private, in the parish churches, the “signs” of our roots. We believe and hope that it's not too late to safeguard a patrimony almost totally extinct and that it is not too late to take back possession of it, to speak of it in a constructive manner. From this analysis, therefore, was born the necessity of a brief written material that has been made possible thanks to the particular sensibility of the present “Amministrazione Provinciale” (Provincial Administration), in the person of the “Assessore” of the “Attività Produttive” (Productive Activity) Dott.ssa Silvia Bernardini. This makes us hopeful that, together with the historical recognition, the institutional obligation, a clear project will mature for the promotion of artistic craftsmanship, that today may find other consumers for its diffusion, to be converted above-all in a work opportunity. From here, the idea that we cannot consider a political and democratic "fabric" open to a social-economic development of the territory without having the capability to “ordire” (put in order) the various elements that characterize it, with the some care that the weaver has in the preparation of their warp. Caring for signifies paying attention to each thread that makes up the “ordito”, furthermore knowing and caring for each part of the various sectors of development of an economy: craftsmanship, agriculture, tourism, to “baste” the development of the territory. Patrizia Ginesi |

|

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

Sulle tracce della tessitura a “liccetti” Un confronto tra prodotto tessile preistorico e contemporaneo dimostra che non ha senso vedere la storia del tessuto come un percorso lineare in termini di progresso tecnico: molti dei materiali, delle tecniche, delle forme in uso nell'antichità lo sono ancora oggi. Ciò che rende il prodotto tessile estremamente complesso e rivelatore dell'ingegno umano è il fatto che nella fabbricazione del tessuto si include anche la creazione della materia prima, diversamente da ogni altra forma di artigianato dove l'uomo interviene sulla materia già esistente quale pietra, legno, terra, .... La storia della tessitura ci aiuta a capire i passaggi evolutivi della tecnologia, dell'agricoltura (uso di corde e strisce di tela per fabbricare aratri, briglie o legamenti per addomesticare gli animali),del commercio, come indicatori di meccanismi culturali, ma si scopre che spesso il saper tessere ne ha stimolato la crescita o la scoperta. |

On the tracks of weaving by “liccetti” A comparison between prehistoric and modern weaving products demonstrates that there is no sense in looking at the history of weaving as a linear journey in terms of technical progress: many of the materials, of the techniques, of the forms used in antiquity are still in use today. That which renders the weaving product extremely complex and revealer of human talent is the fact that in the fabrication of the woven cloth is included also the creation of the prime material, different from any other form of craftsmanship where man intervenes in the material that already exists such as stone, wood, earth... The history of weaving helps us to understand the evolutionary steps of technology, of apiculture (use of rope or strips of cloth to make tapestry, bridles or ligaments for domesticating animals), of commerce, as indicators of cultural mechanisms, but it’s discovered that often knowing how to weave has stimulated the growth or the discovery. |

|

FASCIA DA CARICO: Biella, Collezione Alligni - cm 251x3,3 - Tessuto Inca (sec XV e XVI) Il disegno è formato da una serie di registri di cui si susseguono un motivo zoomorfo stilizzato, rana, un motivo geometrico a doppio rombo e quello della stella a otto punte. |

|

FASCIA DA CARICO Biella, Alligni collection - cm 251x3,3 - Tessuto Inca (XV and XVI centuries) The designs is formedby a series of module followed by a “zoomorfo” (animalform) sketched motif, frog, a geometric design whit a double rhomb and that of the star with eight tips. |

|

Un aspetto ancora più importante è il passaggio evolutivo del tessuto nel rito o tributo, il linguaggio, l'arte, l'identità del singolo. Particolarmente significativo è il rapporto tra tessuto e scrittura: |

A more important aspect is the evolutive passage of woven fabric in the rituals or tribute, the language, the art, the identity of the single. Particularly significant is the relationship between woven fabric |

|

11 |

|

i tessuti trasmettono testi, attraverso di essi si esprime fedeltà, si formulano promesse, (come per le odierne banconote, il cui valore è puramente virtuale) si preservano memorie, si propongono nuove idee. Li potremmo chiamare linguaggi su stoffa: la trama è data da elementi socialmente significativi; la “sintassi” è la costruzione del tessuto. Il tessuto può essere prosa o poesia, testo didattico o indecifrabile. Basta ricordare, in proposito, la valenza narrativa dell'arazzo, che per molti secoli, ancor prima della pittura, assolve un ruolo educativo e comunicativo; sarà il “mercato”, la “committenza” dell'epoca a preferire la rappresentazione pittorica di gran lunga più economica. Ordire è la preparazione dei fili longitudinali attraverso i quali passerà la trama trasversale: operazione questa che richiede una disposizione accurata, ordinata e corretta dei fili da predisporre sul telaio, la quale pregiudicherà l'esecuzione tessile. La parola “ordito” che deriva dal latino, non a caso significa ideazione, preparazione accurata, qualcosa di più del semplice cominciare. Il tessuto nasce dall'incontro di due elementi: ordito e trama. Diversa è la maglia o la rete, dove un unico filo si intreccia su sé stesso. Ciò spiega perché, in senso figurato, la maglia o la rete lasciano intendere un coinvolgimento più violento (presi nella maglia di un imbroglio... cadere nella rete). Tessere no, è l'arte del comporre intrecciando diversi elementi, di cui uno, l'ordito, si apre per accogliere la trama, in un susseguirsi di andate e ritorno, insieme per costruire, formare il tessuto. Il telaio è certamente la macchina più complessa che sia |

and handwriting: woven fabrics transmit writings, through them is expressed faithfulness, promises are formulated, (like the present banknotes, which have a value that is purely virtual) they conserve memories, propose new ideas. We could call them languages on fabric: the “trama” is derived from significant social elements; the “synthesis” is the construction of the woven fabric. The fabric can be prose or poetry, didactic text or undecipherable. We need only remember, in this case, the narrative value of tapestry, that for many centuries, and even earlier with paintings, accomplishes an educative and communicative role; it will be the “market”, the “consumer” of that time period to prefer the pictorial representation which was by-far more economical. Warping is the preparation of the thread in longitude through which will pass the weft perpendicularly: this operation requires an accurate, organized and correct disposition of the thread placed on the loom, that predetermines the textile execution. The word “ordito” (warp) that derives from Lain, not by chance signifies planning, accurate preparation, something more than simply beginning. The woven fabric is created from the encounter of two elements: warp and weft (or woof). This is different from knit or net, where a single thread interlaces within itself. In a figurative sense, it explains why, knit or net makes us understand a more violent involvement. Weaving is the art of composing, interlacing different elements, of which one, the warp, opens to receive the woof, in a succession of coming and going, together to construct, to form the fabric. The loom is certainly the most complex machine that ever |

|

12

|

|

apparsa nell'antichità. Per intrecciare molti fili sottili occorre almeno un telaio a tensione... |

appeared in antiquity. To interlace a multitude of thin threadit is necessary to have at least |

|

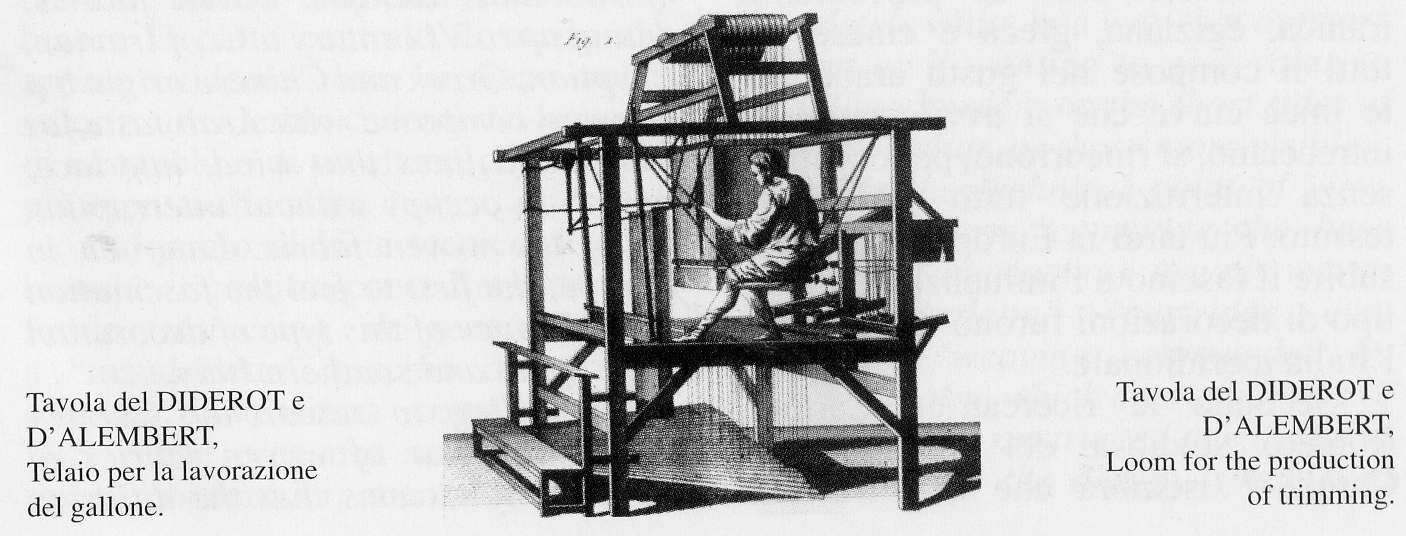

Diverse modalità di tensione hanno dato origine a diversi telai: orizzontali, verticali, a pesi... In seguito l'uso di asticciole o bacchette apripasso e l'introduzione di un licciolo, apparso già nel 1000 a.C., porta decisamente verso una vera e propria tecnica di tessitura. Ad esempio alcune caratteristiche dei telai andini, in particolare l'uso di “aste d’invergatura”, per creare disegni, si riscontrano in tutto il mondo: Scandinavia, Cina, Thailandia, dove questa tecnica sopravvive ancora oggi. Secoli di sperimentazioni e perfezionamenti hanno portato a noi il telaio sostanzialmente invariato fino all'era industriale: dove l'applicazione della forza motrice ed un notevole grado di automazione ha dato luogo, alla fine del XVIII secolo alla rivoluzione industriale. Ai fini del nostro studio interessa lo sviluppo del telaio orizzontale a licci e pedali (dinastia Zhou, 1050-221 a.C.) che consentiva di controllare i licci |

|

a tension loom... Various forms of tension have given birth to various looms: horizontal, vertical, with weights... Followed by the use of small poles or sticks to open the passage and the introduction towards of a “licciolo”, already present in 1000 a.C., brings us decisively a true and proper technique of Weaving. For example, some characteristics of the “andini” looms, in particular the use of "poles of invergatura" to create designs, are found around the world: Scandinavia, China, Thailand, where this technique survives even today. Centuries of experimentations and perfecting brought us the loom substantially unaltered up until the industrial era: where the application of the power engine and a notable level! of automation gave way, at the end of the XVIII century to the industrial revolution. |

|

con il piede, liberando le mani che potevano così lavorare più rapidamente. In Europa, il telaio verticale venne soppiantato da quello a pedali, solo nel Medioevo. Inoltre la distinzione tra disegno per trama e per ordito è cruciale per comprendere gli sviluppi della tessitura a telaio e le armature. Inserendo fili di trama in colore, già in passato, si ottenevano bordi |

For our study, the interest is in the development of the horizontal loom with “licci” (shafts) and pedals (of the Zhou dynasty, 1050-221 a.C. ) that allowed the control of the shafts by foot, freeing the hands that in this way could work more rapidly. In Europe, the vertical loom is replaced by the one with treadles, only in the Middle Ages. Furthermore the distinction between the design by weft and by |

|

|

13 |

||

|

ornamentali. E' noto che le tuniche dei senatori romani erano ornate con un bordo di colore rosso fatto di filo tinto con la porpora. I cardinali della Chiesa Cattolica vengono detti“porporati” in quanto facenti parte di un collegio di uguale dignità di quella dei senatori romani nelle corrispondenti gerarchie. L'uso della trama per ornare e arricchire i prodotti tessili con grossi fili di lana tessuti tramite l'armatura a saia, a formare un rasatello, fornivano tele usate per coperte da letto o “mantili” da tavolo.

1. La decorazione in tessitura. Evoluzione del decoro attraverso la tecnica dei “liccetti”. Il discorso sulla storia della tessitura che vogliamo affrontare in questo breve scritto è limitato unicamente ad una tecnica tessile manuale, che qui preferiamo chiamare semplicemente a “liccetti”, dopo che per troppo tempo è stata ingiustamente denominata solo col termine di “tessuto perugino”. La storia ci insegna che già dal 700-640 a.C., quando in Anatolia cominciano a circolare le prime monete, gli scambi commerciali diventano la ragione primaria delle conquiste territoriali. I tessuti erano fin d'allora beni di scambio importanti, è in questo periodo che la loro fabbricazione e produzione compie il passaggio decisivo: da produzione destinata all'uso a una produzione destinata al profitto. Nell'alto medioevo la tessitura si praticava nell'ambito di una economia curtense. Solo con la creazione delle economie urbane ha acquisito uno sviluppo decisamente artigianale, di rilevanza commerciale, controllato dalle corporazioni specifiche che ne

|

warp is crucial for understanding the developments of weaving with the loom and the armatures. Inserting coloured weft threads, already in the past, produced ornamental borders. It's well-known that the robes of the roman senators were decorated with a border of red colour made with a thread dyed with “porpora” (scarlet). The cardinals of the Catholic Church are surnamed “porporati” for the fact of being part of an order of equal dignity to that of the roman senators in the corresponding hierarchy. Use of the woof to ornament and enrich the woven fabic with thick woollen thread woven through the armature by “saia”, to form a “rasatello”, provided fabrics usedas bed covers or “mantili” or table covers. 1. The decoration of weaving. Evolution of decor through the technique of “liccetti”. The discussion regarding the history o f weaving that we want to deal with in this brief document is limited solely to a manual weaving technique, that here we prefer to call simply by “liccetti”, that for too long has been unjustly called only with the term of “tessuto Perugino” (woven fabric of Perugia). History teaches us that already from 700-640 a.C., when in Anatolia the first currency begins to circulate, commercial exchange becomes the primary reason for territorial conquests. The woven fabrics were since then goods for important exchanges, it is in this period that their fabrication and production accomplishes a decisive step: from a production destined for use to a production destined for profit. In the early Middle Ages, weaving was practised within a “curtense” economy. Only with the creation of the urban economies did it acquire a development decisively artisan, of commercial consideration, controlled by the specific corporations that regulated by aw the dimensions, in |

|

14

|

|

regolamentavano per legge le dimensioni, in modo da essere usate come valuta di scambio. Il commercio poi dei tessuti nel primo Rinascimento ha permesso l'accumulo di ingenti patrimoni e di conseguenza uno sviluppo tecnico della tessitura. Il fenomeno è stato tale che, mentre nei grandi centri come Firenze o Lucca il tessuto ornato con fili di trama in lana veniva sostituito dai più ricchi tessuti con decorazioni in seta, in ambiti periferici si continuava a produrre in modo antico. Infine, l'introduzione del telaio Jacquard (brevettato da Joseph Marie Jacquard nel 1801) spazza definitivamente il vecchio modo di operare manualmente il tessuto decorato. Tramite questo nuovo dispositivo si è potuto aumentare il numero dei “cartoni” per riprodurre disegni sempre più complessi e dettagliati, senza limite: si è così perso il valore evocativo delle figure stilizzate e simboliche dei decori degli antichi tessuti. I cartoni di programmazione non solo hanno rappresentato una grande innovazione nella tessitura, ma hanno avuto un ruolo determinante per la nascita e lo sviluppo dell'informatica! Il meccanismo dei fori pieni e fori vuoti rappresenta la prima forma di codice binario, utilizzato dal precursore e pioniere dell'informatica Charles Babbages per la programmazione della sua “macchina analitica” e sul quale si fonda più tardi il concetto del moderno computer. Col decadere della suggestione simbolica decade anche il valore ornamentale di tale produzione tessile. L'interesse, la curiosità ora è rivolta verso i damaschi e i broccati di seta. L'introduzione del telaio jacquard e della meccanizzazione, confina la tessitura a mano in ambiti sempre più periferici e marginali. |

order to be used as currency exchange. The commerce of woven fabric in the first Renaissance period permitted the accumulation of considerable patrimonies and resulted in a technical development of weaving. The phenomenon was so, that while in the large centres like Florence or Lucca “the decorated woven fabric with weft threads of wool was substituted by richer fabrics that had decorations in silk, the outskirts continued to produce in the antique method”. Finally, the introduction of the Jacquard loom (patented by Joseph Marie Jacquard in 1801) sweeps once and for all the old method of operating manually the decorated woven fabric. Through this new system it was possible to increase the number of “cards” to reproduce designs always more complex and detailed, without limits: in this way was lost the evocative value of the sketched and symbolic figures of the ornaments of antique woven fabrics. The programming cards not only represented a great innovation in weaving, but had a determining role in the birth and development of computer science! The mechanism of the “punched holes and intact holes” represent the first form of binary code, utilized by the forerunner and pioneer of computer programming Charles Babbages for the programming of his “analytical machine” and upon which is later based the concept of computer science! With the decline of the symbolic influence also declines the ornamental value of this type of textile production. Interest, curiosity is now turned towards the damasks and brocades made of silk. The introduction of thejacquard loom and of mechanization, confine hand weaving in to localities always more peripheral and marginal. |

|

15

|

|

|

|

|

|

Con il diffondersi della alfabetizzazione i disegni dei tessuti smisero di “narrare storie” com'era nella tradizione bizantina, per divenire invece decorativi. Ma la trasmissione di generazioni e generazioni di manufatti e iconografie tessili sopravvisse persino alla comparsa di fenomeni di urbanizzazione e di industrializzazione. |

With the diffusion of alphabetisation the designs of woven fabrics stopped “telling storie” as it was in the Byzantine tradition, and become instead decorative. But the transmission from generation to generation of handmade and iconographic textiles survived even up to the appearance of the phenomena of urbanization and industrialization. |

|

|

|

|

Come osserva l'antropologa tessile Maria Luciana Buseghin, nella sua breve relazione: Le opere tessili italiane dal duecento al novecento: il caso dei tessuti umbro - marchigiani “...Taffetas, broccati, lampassi, velluti lisci e operati vennero prodotti, almeno dal Trecento al Settecento, prima soprattutto a Lucca, in seguito anche a Firenze, Genova, Venezia, Bologna... ciò si riferisce soprattutto alla produzione d'arte e comunque a manifatture che lavoravano per ricchi committenti, laici o religiosi che fossero. Per questi ultimi in particolare esistevano anche luoghi di produzione pressoché esclusivi, come per esempio Camerino, che era per importanzala seconda manifattura fornitrice dello Stato |

As observed by the textile anthropologist Maria Luciana Buseghin, in her brief report: Italian textile works from the ‘200’s to the ‘900’s: the case of woven fabrics of umbro - marchigiano. “...Taffeta’s, brocades, lampas, smooth and designed velvets are produced at least from the ‘300’s to ‘700’s, above-all in Lucca, followed by Florence, Genoa, Venice, Bologna...this refers above-all to the art production and in any case to factories that worked for rich buyers, lay people or religious whoever they may have been. For this last category there also existed in particular even places of production almost exclusive, for example Camerino, that was the |

|

16

|

|

|

Pontificio. Ceti popolari e rurali, piccola e media borghesia, contadini, operai, artigiani e mercanti si vestivano e arredavano le loro case con tessuti di minore pregio, spesso di fibre miste, prodotti in manifatture locali che andavano dal laboratorio domestico a quello artigianale. Ciò costituiva in alcuni casi una struttura economica di tipo paleo- capitalista con un'organizzazione e una divisione del lavoro che comprendeva anche, la costituzione di società imprenditoriali, dal filato alla commercializzazione del prodotto finito...”. Per tutto il periodo dell'arte romanica era ancora poco sviluppata la fabbricazione di telerie con figurazioni ornamentali. Si ha notizia solo di tessuti in lino per uso ecclesiastico, tovaglie d'altare con ornamento ai bordi decorate. I pochi tessuti rimasti risalenti al l’Xl e XII secolo (periodo di transizione dell'arte romanica a quella gotica) mostrano scarsa originalità ed una tendenza a riprodurre ornamenti con disegni geometrici di evidente derivazione saracena. La tessitura bizantina che pure era conosciuta in occidente per i commerci delle repubbliche marinare, perdette importanza dopo il crollo del 1204, ma dopo la presa di Bagdad, da parte dei mongoli nel 1258 e specialmente con la Signoria di Tamerlano del 1402, si ebbe una ripresa delle relazioni commerciali con il medio ed estremo oriente. Furono allora conosciute espressioni d'arte orientali e si diffuse anche un gusto di ornamenti di tipo naturalistico di ispirazione cinese, con figurazioni stilizzate di mostri, draghi, piante... Ma la tessitura italiana nel corso del XIV secolo pur conservando tali motivi iconografici, si evolve sotto gli influssi del gotico

|

second most important supplier for the Papal State. Popular and rural classes, low and middle class bourgeoisie, farmers, working class, artisans and merchants clothed themselves and furnished their homes with woven fabrics of lower quality, frequently made of mixed fibres, produced in local factories which ranged from domestic to artisan workshops. This constituted in some cases a type of economic structure “paleo-capitalista” with an organization and a division of work that included even, the constitution of an entrepreneurial company, from threading to the commercialisation of the finished product...”. For all of the period of the Romanic art the production of linen and cotton goods with ornamental figurations was still developed very little. The information available refers only to linen fabrics for ecclesiastic use, altar covers with borders decorated with ornaments. The few fabrics remaining dating back to the XI and XII centuries (transition period from Romanic to the gothic art) show little originality and a tendency at reproducing ornaments with geometric designs clearly deriving from Saracen. Bizantine weaving that was also known in the west because of the trades of the “repubbliche marinare”, lost importance after the downfall in 1204, but after the conquest of Baghdad, hy the Mongols in 1258 and especially with the domination of “Tamerlano” of 1402, there was a rebirth of the trading relations with the middle and extreme orients. The artistic expression of oriental arts was therefore known and there also spread a taste for naturalistic type ornaments deriving of Chinese inspiration, with sketched figurations of monsters, dragons, plants... But Italian weaving in the course of the XIV century while

17

|

|

settentrionale (la stagione compresa fra la fine del Trecento e la metà del Quattrocento) cui è stata attribuita la definizione di Gotico Internazionale, segna uno dei momenti più significativi della storia artistica europea: un comune linguaggio figurativo attraversa la Francia, la Boemia, la Lombardi, l’Emilia e le Marche, sino ad acquisire una propria individualità raffinata rimasta pressoché inalterata fino all'avvento di tecniche di lavorazione innovative.

|

conserving these iconographic motifs, evolved under the northern gothic influences (the season including the end of the ‘300’s to the middle of the ‘400’s), to which it was attributed the definition of International Gothic, marks one of the most significant moments of the artistic history in Europe: a common figurative language passed through Franco, Bohemia, Lombardia, Emilia and the Marche, up to acquiring it's own refined individuality remaining almost unaltered up until the advent of innovative working techniques.

|

|

|

|

2. Le “tovagliette”: dimostrazione dell'importanza della tradizione attraverso la longevità di alcuni motivi decorativi. Molti studiosi, dal 1800 ad oggi, si sono occupati di questa tipologia tessile, sia per ricercarne le origini che per analizzarne le decorazioni. Tra questi lo storico Walter Bombe, che in un opuscolo intitolato “Studi sulle tovaglie perugine” ripercorre 1'evoluzione dell'icono-grafia mediorientale in Italia: “...prima del 1200, stoffe simili a quelle bizantine erano già presenti in Italia, ma sottoforma di pedissequa imitazione di queste ultime, perciò considerate di scarso valore. |

2.The “tovagliette”: demonstration of the importance of the tradition through the longevity of certain decorative motifs. Many scholars, since the 1800's up to today, have occupied themselves with this type of textile, to research its origins as well as to analyse its decorations. Among these the historian Walter Bombe, who in a booklet entitled “Studi sulle tovaglie perugine” (Studies of the tablecloths of Perugia) traces the evolution of the mid-oriental iconography in Italy: “...before the 1200's, cloths similar to those Byzantine were already present in Italy, but under the form of pureimitation of these |

|

18

|

|

Successivamente, nel corso del XIV secolo, i tessuti italiani divennero più interessanti poiché risultavano un'affascinante combinazione tra l'influenza bizantina e gusto gotico settentrionale: le figure rappresentate erano caratterizzate da schematismo e semplicità cosicché i disegni risultavano creazioni fantastiche e non necessariamente aderenti alla realtà, non solo nella figura, ma anche nella loro ambientazione...”. Oppure, l'antropologa tessile Maria Luciana Buseghin, la quale così descrive tali manufatti: “...è proprio questo il caso di particolari tessuti in lino bianco e cotone turchino, solitamente con armatura di fondo a “occhio di pernice” e/o spina e la decorazione a fasce di trame serrate e lanciate. Prodotti in Italia centrale, soprattutto nell'area dell'Appennino umbro-marchigiano, almeno a partire dal Duecento ed esportati, almeno fino al Cinquecento, in tutta Europa, sono oggi generalmente conosciuti con il termine di “tovaglie perugine”. |

last mentioned, thus considered of little value. Subsequently, in the course of the XIV century, Italian woven fabrics became more interesting as they resulted in being a fcinating combination between the Byzantine influence and the taste of northern gothic: the figures that were represented were characterized by schematism and simplicity in order that the designs resulted in fantastic creations and not necessarily true to reality, not only in the figure but also in their environments...”. As well, textile anthropologist Maria Luciana Buseghin, who describes in this way this handmade product: “...it is actually this the case of particular woven fabrics of white linen and turquoise cotton, usually with an base armature of “partridge eye” and/or “spina” and the decoration in strips of tight and launched weft. Produced in central Italy, mainly in the umbro-marchigiano Apennine area, at least since the '200's and exported, at least up until the '500's, in all of Europe, they are generally known today as “tovaglie perugine”. |

|

|

|

19

|

|

|

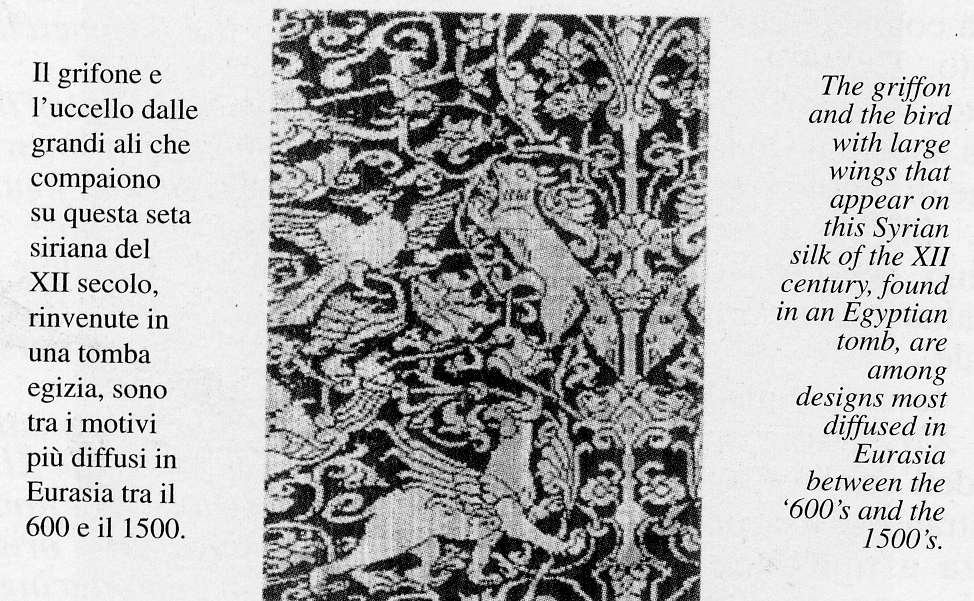

Hanno costituito e costituiscono talvolta un tema di scontro tra studiosi umbri e marchigiani: nelle Marche, dove si producevano, e si producono ancora, a Macerata, Matelica, Pievebovigliana, questi affascinanti tessuti vengono considerati vanto regionale e detti “tovagliette marchigiane”. Del resto manufatti tessili pressoché identici per tecnica e disegno si trovano in Toscana, Marche, Abbruzzo, Carnia (Friuli), Trentino Alto Adige... fatto che pone la problematica questione della loro diffusione nello spazio e nel tempo e della eventuale produzione locale su modello estero o su insegnamento di maestri importanti. Quanto all'uso, si può dire che hanno costituito nei secoli sostanzialmente tessuti per arredamento e per l'abbigliamento maschile e femminile, spesso parte integrante di corredi da sposa e asciugamano di uso sacro e profano, tende, copriportiere, cuscini, coprisedili, scialli da testa, e da spalle, cinture, fusciacche, bisacce a doppia sacca, turbanti e “sciuccatori” arrotolati con funzione di appoggio per le ceste da portare sopra la testa; talvolta anche stendardi - premio nei cortei cavallereschi, con tessuto il nome della bella o il motto per cui si combatteva... “Queste opere tessili sono largamente raffigurate nei dipinti e nelle sculture lignee degli artisti medievalrinascimentali, anche se non mancano iconografie tessili assai simili già nei mosaici del V - VI sec. d.C: per esempio nelle basiliche bizantine di Santa Apollinare e San Vitale a Ravenna, ma anche nelle catacombe romane del III secolo o delle chiese romaniche della Puglia...” La maggior parte degli autori mettono in evidenza influenze vicine e/o estremo orientali, soprattutto per quanto riguarda la struttura di alcuni motivi decorativi: drago, grifo, palmette o rosette... gusto considerato orientaleggiante fin dall'epoca etrusca.

|

They have and continue to constitute from time to time a topic of controversy among umbri and marchigiani scholars: in the Marche, where they were produced and continue to be produced, in Macerata, Matelica, Pievebovigliana, these fascinating woven fabrics are considered the boast of the region and called “tovagliette marchigiane”. Moreover, handmade fabrics almost identical in technique and design can be found in Toscana, Marche, Abbruzzo, Gamia (Friuli), Trentino Alto Adige... a fact which poses the problematic question of their spreading in space and time and of the eventual local production based on a foreign model or on the teaching of important masters. As far the use, it can be said that they have constituted substantially over the centuries woven fabrics for furnishing and also for male and female clothing, often integrating parts of bride dowries and towels for sacred and secular use, curtains, door curtains, pillows, chair covers, head and shoulder shawls, belts, sashes, double pouch saddlebags, turbans and “sciuccatori” (cloths) rolled up with the function of support for baskets carried on the head; at times even banners - prizes in the knight courts, in which was woven the name of the beauty or the motto for which they competed... “These textile works are largely refigured in paintings and in wooden scriptures of the artists of the Middle Ages and Renaissance era, even if there is no lack of iconographic textile very much similar already in mosaics of the V - VI centuries d.C.: for example in the Bywntine basilicas of Santa Appolinare and San Vitale in Ravenna, but even in the roman catacombs of the III century or of the roman churches of Puglia...” Most authors highlight near and/or extreme oriental influences, above all with regards to the structure of a few decorative motifs: dragon, griffon, small palms or roses.... considered of oriental taste up until the |

|

|

|

|

20

|

|

Questo ci pone ancora una volta di fronte alla questione dei traffici commerciali e delle rotte marittime che collegavano occidente e vicino oriente attraverso il Mediterraneo e della grande importanza che hanno avuto in tutto ciò le Crociate fonte di scambi commerciali e culturali tra Terra Santa ed Europa che divenne un vero e proprio reliquario, come dimostrano i tanti tessuti che sono arrivati a noi come contenitori di sacre parti del corpo dei santi e della Croce. Fa notare inoltre la Buseghin come: “... grazie alle ricerche storico - archivistiche di Ariel Toaff, e ai suoi interessanti saggi sui mercanti e artigiani ebrei, che i tessuti bianchi e blu, piuttosto che perugini, umbri, marchigiani, costituiscono una produzione tipica delle comunità ebraiche stanziatesi in Umbria e nelle Marche, i cui componenti lavoravano in società con cristiani per i quali era più facile svolgere una serie di ruoli per la produzione, il deposito e la rivendita di tessuti. Agli ebrei spesso non era permesso di far parte delle Corporazioni delle Arti o altro organo ufficiale: e questo dato potrebbe in parte spiegare la carenza di documentazione archivistica da parte cristiana relativamente alla produzione di “tovagliette”. Proprio la forte presenza di queste comunità nel Centro Italia e la loro attività prevalentemente di produttori e commercianti di tessuti, ha dunque, con molte probabilità, determinato l'accoppiamento di colori caratteristico e dominante nei tessuti.

Bianco e blu, sono in molte culture colori riservati alla

divinità e alla classe sacerdotale: dagli dei egiziani con parrucca e barba

azzurro cupo che simboleggiano le forze cosmiche, ai drudi, sacerdoti dei

Celti, alle divinità indù Krishna e Shiva rappresentate |

end of the Etruscan epic. This poses us once again in front of the question of commercial trading and the maritime routes which connected the west and dose orients through the Mediterranean and of the big importance that the Crusades had in all of this, source of commercial and cultural trades between the Holy Land and Europe that became a real and proper reliquary, demonstrated by the many fabrics which arrived to us as containers of holy relics of saints and of the Cross. Buseghin points out further how: “...thanks to the historical research - archivist Ariel Toaff, and his interesting essays on Hebrew merchants and artisans, that the white and blue woven fabrics, mainly perugini, umbri, marchigiani, constitute a typical production of the Hebrew community settled in Umbria and in the Marche, of which members worked together with Christians for whom it was easier to carry out a series of roles for the production, the Storage and the resale of woven fabrics. To the Hebrews it was not often permitted to be part of the “Corporazioni delle Arti” (art corporations) or other official bodies: and this fact could in part explain the lack of archived documentation on the part of Christians relative to the production of “tovagliette”. Exactiy the strong presence of this community in Central Italy and their activity predominately as producers and merchants of woven fabrics, determined as a result, with much probability, determined the matching of colours characteristic and dominant in woven fabrics. White and blue, are in most cultures colours reserved for divinity and the priestly classes: from the Egyptian gods with wigs and beards of blue which symbolized the cosmic forces, to druids, Celtic priest, to Hindu Krishna and Shiva divinities represented in blue and white blue, but maybe the explicit |

|

|

|

|

21

|

|

|

in blu e bianco blu, ma forse la esplicita e precisa canonizzazione e conseguente applicazione sull'uso dei colori, si trova nel Libro dei Numeri, quarto libro del Pentateuco, contenuto sia nella Bibbia che nella Torà. Nel Libro dei Numeri, si narrano le vicende storiche del popolo ebreo: Mosè parla agli Israeliti perché ponessero dei nocchi o frange o nappe alle estremità delle vesti, in particolare degli scialli di preghiera perché vedendoli ricordassero tutti i precetti del Signore e li praticassero. Alle frange poste negli angoli dovevano essere inseriti fili di colore techelet che, viene tradotto con blu o porpora, e con il quale comunque in lingua ebraica s’intende riferirsi a varie sfumature dal blu scuro al violaceo; al blu giacinto; all'azzurro- turchino (colore dominante del Dio ebraico-cristiano). Le cosiddette "tovaglie perugine - marchigiane” che erano usate anche come sottotovaglie d'altare, spesso erano ornate da frange del tutto simili a quelle descritte...”. Testimonianza della diffusione di questa arte, come già ricordato, si ritrova, quindi, nei dipinti dei maestri del XIII e XIV secolo; dove essi rappresentano episodi del vecchio e nuovo Testamento o ritraggono scene di vita familiare in interni. Sono quadri o affreschi che hanno per soggetto: Ultime Cene, nozze di Caanas, danze di Salomè, ecc. Ricordiamo in proposito il famoso affresco di Giotto nella Chiesa superiore di San Francesco in Assisi, intorno al 1300, che illustra “La profezia al Cavaliere di Celano”, dove è chiaramente raffigurata una tovaglia, decorata, nei lembi dei lati corti, con due liste di colore turchino. E ancora di Giotto le “Nozze di Cana” a Padova, Cappella degli Scrovegni, dove la tovaglia risulta ornata alle estremità da

|

and precise canonization and consequent application of the use of colours, con be found in the Book of Numbers, fourth book of the Pentateuch, contained in the Bible as well as the Torah. In the Book of Numbers, is narrated the historical events of the Hebrew people: Moses talks to the Israelites so that they may place bows or fringes or tassels on the hems of their garments, in particular the prayer shawls so that seeing them everyone would remember the precepts of the Lord and practice them. To the tassels placed at the angles there had to be inserted threads of “techelet” (violet) colour that, becomes translated with blue or scarlet, and with which always in the Hebrew language intends to indicate a variety of shades from dark blue to violet; to hyacinth-blue; to blue-turquoise (dominant colour of the Hebrew-Christian God). The so-called “tovaglie (tablecloths) perugine – marchigiane” that were used also as altar covers, were often decorated with tassels in all similar to those described...”. Testimony of the diffusion of this art, as al ready remembered, can be found, therefore, in paintings of the masters of XIII and XIV centuries; where they represent episodes of the old and new Testaments or scenes of interior family life. They are pictures or paintings that have as subject: the Last Supper, the wedding at Cana, the dance o f Salomé, etc. We remember in this case the famous wall-painting of Giotto in the Chiesa superiore di San Francesco in Assisi, around the 1300's, which illustrates “The prophecy to the Knight of Celano”, where is clearly depicted a tablecloth, decorated, in the borders and short sides, with two turquoise coloured strips. And again of Giotto, the “Wedding at Cana” in Padova, Cappella degli Scrovegni, where the tablecloth is decorated at the extreme ends

|

|

|

|

|

22

|

|

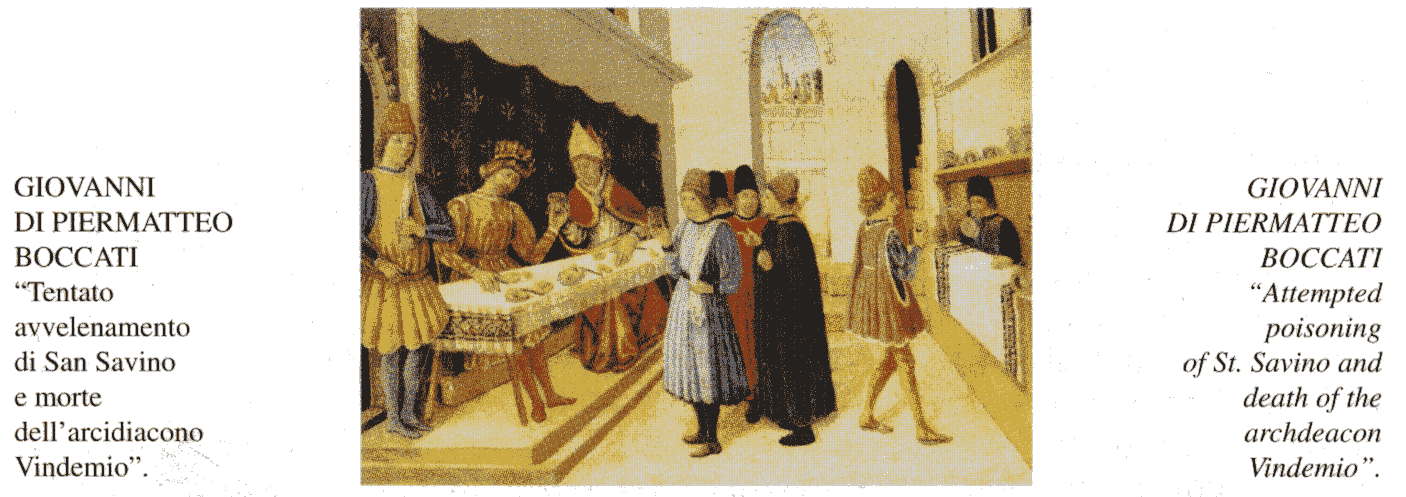

una serie di uccellini affrontati. Oppure, Pietro Lorenzetti, nella “Nascita della Vergine”, Siena, Opera del Duomo, dove si nota l'asciugamano coi bordi decorati. Mentre nel “Frate che rifiuta l'amputazione”, Firenze, Uffizi, è la coperta da letto ad avere le fasce ornate in colore. Di Simone Martini, “S. Martino celebra la messa”, in Assisi, Chiesa inferiore di S. Francesco, la tovaglia d'altare presenta il decoro con gli uccelli in fila. Oppure il nostro Antonio da Fabriano, 1452, “Crocifisso”, Matelica, Museo Piersanti, dove il perizoma del Cristo mostra liste decorative in blu. E ancora, un artista di Camerino, Giovanni di Piermatteo Boccati, una tempera su tavola, che si trova ad Urbino presso la Galleria Nazionale delle Marche: “Tentato avvelenamento di San Savino e morte dell'arcidiacono Vindemio” - 1473, docu-mentato a Camerino dal 1445, il quale descrive il gusto decorativo di tovaglie da mensa con bordi laterali in blu su disegno geometrico. Nell'iconografia classica del Cenacolo, con gli apostoli ed il Cristo riuniti intorno ad un tavolo stretto e lungo, i pittori hanno spesso rappresentato la scena evidenziando tovaglie dai bordi riccamente decorati in trama. Tale caratteristica la possiamo osservare, solo per citarne alcuni dei maggiori, in: |

|

with a series of small birds facing each other. Or also, Pietro Lorenzetti, in the “Birth of the Virgin”, Siena, Opera del Duomo, in which there is a towel with decorated borders. While in the “Friar who Refuses Amputation”, Firenze, Uffizi, it is the blanket which has strips decorated in colour. Qf Simone Martini, “S. Martino celebrates the mass”, in Assisi, Chiesa inferiore di S. Francesco, the altar tablecloth presents a decoration with birds in a row. Or also “our” Antonio da Fabriano, 1452, “Crocifisso”, Matelica, Museo Piersanti, where the loin-cloth of Christ shows decorative strips in blue. As well, an artist of Camerino, Giovanni of Piermatteo Boccati, a water-painting on wood, that is found in Urbino near the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche: “Attempted poisoning of St. Savino and death of the archdeacon Vindemio” - 1473, documented at Camerino from 1445, who describes the decorative taste of tablecloths with lateral borders in blue in geometric design. In the classical iconography of the “Cenacolo” (Last Supper Room), with the apostles and Christ gathered around a long and narrow table, painters have often represented the scene evidencing tablecloths with borders richly decorated in weft. We can observe this type of characteristic, listing only a few of the most important ones, in: |

|

23

|

|

• Duccio da Boninsegna, Siena, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo; • Ghirlandaio, Firenze, Chiesa di Ognissanti e Museo S. Marco; • Leonardo, Milano, S. Maria delle Grazie; Parigi, Louvre; • Andrea del Sarto, Firenze, S. Salvi; • Perugino, Firenze, Convento di Foligno. |

• Duccio da Boninsegna, Siena, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo; • Ghirlandaio, Firenze, Chiesa di Ognissanti e al Museo S. Marco; • Leonardo, Milano, S. Maria delle Grazie; Parigi, Louvre; • Andrea del Sarto, Firenze, S. Salvi; • Perugino, Firenze, Convento di Foligno. |

|

|

|

|

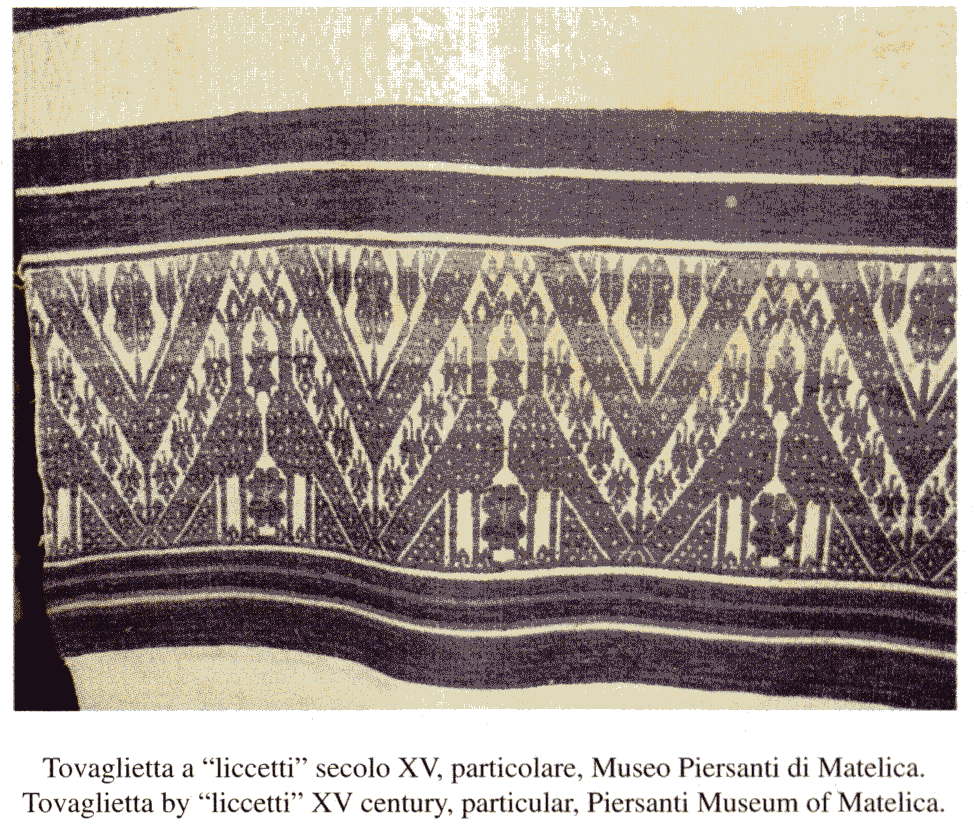

I primi ornamenti con figure che appaiono ai bordi di tovagliette, la cui ridotta larghezza era pari a quella dei tavoli stretti e lunghi tipici del medioevo, erano usate sia per ricoprire nella casa un tavolo, una credenza, una cassapanca, come per ricoprire gli altari, motivo questo che ne ha consentito una lunga conservazione. La decorazione si concentra su fasce che corrono da una cimosa all'altra, intervallate da brevi spazi bianchi, mentre è lasciata interamente bianca la parte centrale di modo che appare evidente come si siano voluti valorizzare i lembi cadenti dei lati corti di un tavolo o di un altare, come quelli più esposti alla vista. Dal punto di vista tecnico, le parti bianche, costituiscono l'armatura di fondo (intreccio), in genere tessuta a "mandorletta" (occhio di pernice) schema di tessitura comandato dai “licci” che crea una serie di piccoli rombi concentrici, mentre il disegno

|

The first decorations with figures that appear on borders of “tovagliette”, of which the reduced width was equal to that of the typical long and narrow tables of the Middle Ages, were used to cover in the home a table, a cupboard, a chest, as for covering altars, this being the reason of their lengthy conservation. The decoration is concentrated on strips which run from one selvage to the other, with intervals of brief white spaces, while the central part is left completely white in a way that appears evident as if wanting to give value to the falling borders on the short sides of a table or altar, as those more visible. From the technical point of view, the white parts, constitute the base armature (interlacing), usually woven in “mandorletta” (partridge eye) pattern of weaving commanded by “licci” (shafts) which create a series of small rhombs constructed one inside of another, while the design is achieved through the movement |

|

24

|

|

|

si realizza tramite il movimento dei “liccetti” preparati sul telaio secondo lo schema della “messa in carta”. Gli ornamenti sono inizialmente di semplici forme geometriche: greche, quadrati, losanghe che si ripetono in più ordini. Lo sviluppo dei motivi decorativi prende in esame un unico modulo, disegno base, che si ripete a specchio per tutta l'altezza del tessuto. Sono disegni stilizzati di animali come uccellini, aquilette, cagnolini,... la cui altezza delle figure è limitata, tale da costituire solo fasce di bordure. Quando il disegno si è fatto più alto, cioè realizzato con un maggior numero di “liccetti”, (il numero dei liccetti era uguale a quello delle trame ad evoluzione diversa, necessarie per la realizzazione del disegno) la figura si è fatta simbolica coerente con l'uso al quale era destinato il manufatto. Fregi geometrici, quali tratteggi, scacchiere, losanghe, sottolineano la figura o rappresentazione principale, solitamente animaliera, per rendere armonica l'intera composizione. Come si è già detto, durante il Medioevo si diffusero in Italia tecniche e motivi ornamentali strettamente legata all'immagina-rio islamico, che a loro volta trassero molteplici motivi animalieri e vegetali nei fregi di più antichi tessuti, risalenti fino al VI secolo a.C. di provenienza iranica, egiziana, greca e cinese ma tutti li compose nel gusto arabo per le linee curve che si avviluppano, si intrecciano, si rincorrono, per occupare senza interruzione tutto lo spazio tessuto. Più tardi in Europa, le prime a subire il fascino e l'influenza di questo tipo di decorazioni furono la Spagna e l'Italia meridionale. Secondo la ricercatrice Carmen Romeo, studiosa dei tessuti della Carnia, “...sembra che la diffusione di questa tecnica Europa si |

of “liccetti” prepared on the loom according to the pattern of the “messa in carta” (drafted outline). The ornaments are initially of simple geometric form: “greche”, squares, rhombs that repeat in more sequences. The development of the decorative motifs take in examination a single modulo, base design, that repeats in reflection (as in a mirror) for all the height of the woven fabric. They are designs drawn from animals like small birds, eagles, dogs,... of which the height of the figures is limited, in order that they constitute only strips of bordering. When the design is made higher, in other words realized with a major number of liccetti, (the number of liccetti are equal to that of the weft of different evolutions, necessary for the achievement of the design) the figure is made symbolic according to the use for which the hand made item is destined. Geometric ornaments, such as dotted lines, squares, rhombs, underline the figure or main representation usually of animals, to render more harmonious the entire composition. As it has already been said, during the Middle Ages there spread in Italy techniques and decorative motifs closely tied to Islamic imagery, that in their turn took numerous animal and vegetal motifs from the ornaments of the most antique woven fabrics, dating up to VI century a.C. of Iranian, Egyptian, Greek and Chinese origin but all were composed with Arab taste for the curved lines that wind, interlace, repeat, to occupy without interruption all of the woven fabric. Later on in Europe, the first to feel the fascination and influence of this type of decoration were Spain and southern Italy. According to researcher Carmen Romeo, scholar of woven fabrics of Carnia, “..it seems that the diffusion of this technique in Europe is owed to German weavers of fustian that in the last quarter of the XIV |

|

|

|

|

|

25

|

|

debba ai tessitori tedeschi del fustagno che nell'ultimo quarto del XIV secolo portarono da Venezia, attraverso le Alpi l'arte di tessere tessuti in lino e cotone: le stoffe del centro Italia vennero così imitate dai tedeschi del sud. In chiese ungheresi sono presenti queste stoffe; sia antiche sia di produzione popolare recente: originariamente tessute con l'impiego di numerose bacchette (liccetti), da sessanta a centoventi circa...”. Si vengono presto a definire due sostanziali differenze tra la produzione tessile dei “liccetti” locali e quella del resto d'Italia: in primo luogo c'è la scelta del filato, più modesto e semplice nel primo caso (cotone lino), sfarzoso nel secondo caso (seta e fili d'oro). Anche le tecniche di tessitura, basandosi sugli stessi principi, presentano delle differenze. Nelle sete italiche la decorazione occupava in genere tutto il tessuto, di conseguenza tecnicamente più elaborata, non permetteva l’uso dei “liccetti” dotati di semplici canne d'india . I “liccetti” c'erano, ma collegati ad una struttura che sovrastava il telaio e sollevati da un'assistente “tralicci” da un soppalco posto sul telaio, nei telai più antichi, o attaccati a corde che pendevano lateralmente al telaio e azionate sempre da un'aiutante.

|

century brought from Venice, through the AIps, the art of weaving fabrics in linen and cotton: the cloths from central Italy became in this way imitated by Germans in the south. In the Hungarian churches these cloths are present; both of antique as well as recent popular production: originally woven with the use of numerous small rods or sticks (liccetti), from sixty to around one hundred and twenty...”. We can quickly define two substantial differences from the textile production using “liccetti” and that of the rest of Italy: in the first place there is the choice of thread, more modest and simple in the first case (cotton and linen), luxurious in the second case (silk and golden thread). Even the weaving techniques, basing themselves on the same principles, present differences. In the Italian silks the decoration occupied usually all of the woven fabric, consequently more technically elaborate, did not permit the use of “liccetti” made of simple bamboo sticks. The “liccetti” existed, hut connected to a structure which is above the loom and raised by an assistant “tralicci” of a “soppalco” placed on the loom, in the more antique looms, or attached by cords that hung laterally on the loom and set in motion always by a helper.

|

|

|

|

|

26

|

|

|

La tessitura a “liccetti” pendenti sotto il peso di canne d'India, “le canne sotto l’ordito” come amava chiamarle la scomparsa Maria Ciccotti, ci sembra una peculiarità marchigiana: probabilmente la tecnica nacque dalla necessità di semplificare il lavoro riducendo i tempi di manodopera, infatti i tessuti presi in esame presentano solo fasce decorate che hanno bisogno di un minor numero di “liccetti”: le cannette sono facili da reperire e leggere; inoltre è sicuramente più agevole abbassare i fili d’ordito piuttosto che alzarli! L'iconografia del ricco bestiario, creato fra verismo e fantasia e sempre con gusto raffinato del disegno, si mantenne inalte-rato, nelle sue serie ripetitive di sagome affrontate o opposte, per il lungo continuo apporto di maestranze arabe nell'arte della tessitura italiana; ma bisogna riconoscere che si è conservato a lungo nel mondo occidentale in quanto si caricò presto di simbolismo cristiano. Frequenti sono le figurazioni di leoni, draghi, aquile, grifoni, pavoni, uccelli; seguono sempre più rari l'unicorno, il cervo, il centauro, l'arpia. Una delle figure allegoriche rappresentata in molteplici versioni è l'albero della vita: stilizzazione di un albero a cono rovesciato, il quale reca frutti rituali (fiore o grappoli d'uva, pampini di vite...) e simboleggia il ciclo dell'esistenza: tutti soggetti di forte significato religioso cristiano. Albero più o meno stilizzato, che riappare a marcare la scansione delle figure ispirate ad animali reali o chimerici, ripresi sempre in coppia, affrontati. Le riproduzioni animaliere che più caratterizzano questa tipologia tessile si possono riassumere così schematicamente: • il drago, animale chimerico, dalla testa di sauro, zampe unghiate, |

Weaving by “liccetti” hanging under the weight of canes of India, “le canne sotto l’ordito” as were affectionately named by the late Maria Ciccotti, seem to be for us a marchigiana peculiarity: probably the technique was born from the necessity to simplify the work reducing the times of manpower, in fact the woven fabrics observed present only decorative strips that need to be of a minimum number of “liccetti”: the small sticks are light and easy to find; in addition it is certainly more agile to lower the threads of warp than to raise it! The rich iconography of animal designs, created from realism to fantasy and always with refined taste for design, is maintained unaltered, in its repetitive series of shapes facing or opposing each other, for the long continuous contribution of Arabian manpower in the art of Italian weaving; but we need to recognize that it has been conserved at length in the western world for having quickly taken on Christian symbolism. Frequent are the designs of lions, dragons, eagles, griffons, peacocks, birds; accompanied by those that are always more rare of the unicorn, deer, centaur, harpy. One of the allegorical figures represented in the multiple versions of the tree of life: representation of an inverted tree which produces ritual fruit (flowers or clusters of grapes, vine-leaves..) and symbolizes the cycle of existence: all subjects of strong Christian religious significance. Tree more or less sketched, which reappears to mark the sequence of the figures inspired to realistic or imaginary animals, always represented in two, facing each other. The animalistic reproductions that most characterize this type of textile can be reassumed schematically in this way: • the dragon, imaginary animal, from the head of sorrel, |

|

|

|

|

|

27

|

|

ali e coda di serpente. Tipico della cultura cinese, simbolo di prudenza e fedeltà; • Nell'araldica medievale simbolo dei ghibellini; nella simbologia cristiana simbolo del male; • il grifo, animale chimerico, mezzo aquila e mezzo leone. Versione tipica della cultura perugina del drago, simbolo della città di Perugia; • l'arpia, metà donna e metà uccellaccio, soggetto della mitologia greca; • il centauro, metà uomo e metà cavallo, soggetto della mitologia greca; • l'unicorno, fantastico animale simile ad un cavallo con un lungo collo e un corno in fronte. Essere selvaggio e pericoloso che poteva essere ammansito solo da una pura vergine, nella cultura cinese. Nella cristianità è simbolo di verginità e raffigurato in onore di Maria; • il leone, ripreso in vari atteggiamenti: rampanti, in piedi, acco-vacciati; nel simbolismo maomettano raffigura il sovrano o la sovranità, diviene metafora di Gesù nell'occidente cristiano simbolo della tribù di Giuda e quindi anche di Cristo; • l'aquila, simbolo di sovranità, molto comune nell'araldica; • la colomba, simbolo della pace e dello Spirito Santo, l'anima nella cristianità, nell'antichità era riferita a Venere; • il pavone, gallinaceo originario dell'India, importato in occidente ai tempi di Alessandro Magno; simbolo di maestà, ricchezza e lusso; simboleggia la ruota solare e l'immortalità.

|

clawedpaws, wings and tail of a serpent. Typical of the Chinese culture, symbol of prudence and fidelity; In the heraldry of the Middle Ages symbol of the “ghibellini”; in the Christian symbolism a symbol of evil. • the griffon, imaginary animal, half eagle and half lion. Version typical of perugina culture of the dragon, symbol of the city of Perugia; • the harpy, half woman and half bird, under Greek mythology; • the centaur, half man and half horse, subject of Greek mythology; • the unicorn, fantastic animal similar to a horse with a long neck and a horn in front. Wild and dangerous animal that could be calmed only by a pure virgin, in the Chinese culture. In Christianity it is the symbol of virginity and refigured in honour of Mary; • the lion, designed in various positions: raging, standing, crouched; in Arabic symbolism represents the sovereign or sovereignty, in western Christianity it becomes a metaphor of Jesus, symbol of the tribe of Judah and therefore also of Christ; • the eagle, symbolizes sovereignty, very common in heraldry; • the dove, symbol of peace and of the Holy Spirit, the soul in Christianity, in antiquity it was referred to Venere. • the peacock, originally from India, imported in the west in the period of Alessandro Magno; symbol of majesty, richness and luxury; symbolizes the solar route and immortality.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

28 |

|