|

|

|

January 20, 1985 - Stanford Stadium, Stanford

San Francisco

49ers 38

Miami Dolphins

16

No question about it, this was one Super Bowl that couldn't miss.

Forget about all the past Super Bowls that had turned out to be one-sided flops; not only were the two best teams in the National Football League in 1984 matched, but so were the two best quarterbacks. Surefire box office material, this one.

You wanted points? You wanted excitement? Tune in. You wanted defense? Turn the channel.

Unfortunately, real life isn't like old-time Hollywood, where dreams come true and everyone rides off into the sunset for a happy ending. Instead of getting the drama of "Gone With the Wind" and the excitement of "Ben-Hur," the largest viewing audience in television sports history was treated to a high-budget production of "Godzilla Meets the Sea Mammals." It was a laugher.

Matinee idol Dan Marino didn't win an Oscar for his performance. Nor did the Miami Dolphin defense, which found itself vastly overmatched against a quiet guy named Joe Montana and an excellent supporting cast. The Dolphins gave more than 115 million TV viewers and 84,059 spectators at Stanford Stadium a B movie at best.

Ah, but the San Francisco 49ers. What grace, what class, what an award-winning performance. They demolished the Dolphins, 38-16, in Super Bowl XIX, and in so doing taught football fans two valuable lessons: One, even the most promising of Super Bowl matchups seldom live up to expectations, and two, defenses still hold the key to these championship games.

As good as Montana was -- and he was astonishingly effective and productive -- it was the 49er defense that performed the miracle of Super Bowl XIX, thereby taking the luster off Marino's rising star.

This was the same Marino who had shown absolutely no respect for the NFL's regular-season record book. A second-year quarterback, Marino still should have been learning the game, but instead he was collecting unprecedented passing totals that pinpointed him as the best quarterback in the league.

Marino became the first player ever to throw for 5,000 yards (5,084) in a season. He shattered the NFL record for touchdown passes in a season with 48, and his 362 completions and four 400-yard games also were league records. He led the league in pass attempts, average yards per completion and efficiency rating. Entering the Super Bowl, he had passed for at least one touchdown in each of his last 22 games, including four in an overwhelming performance against Pittsburgh in the American Conference championship game.

Marino was the conductor of one of the most proficient offenses in NFL history, one that was averaging more than four touchdowns per game. So, it was no surprise that wherever the blond wonder boy went during Super Bowl week, he generated the kind of excitement that usually is associated with rock stars. Even the news that he was engaged failed to cool down his adoring female fans.

Stationed in Oakland, across the bay from the 49ers, the Dolphins were anything but lost amid the hometown hysteria of fans in the San Francisco area. For Montana, who is not particularly comfortable in the spotlight, it was a welcome relief to have Marino and the Dolphins capture the bulk of the pregame publicity. Yet there comes a point when enough is enough.

The 49ers had every right to feel slighted. After all, it wasn't as if they had lucked their way into the Super Bowl. Their 15 regular-season victories constituted an NFL record, and their decisive 23-0 victory over Chicago in the National Conference title game had been impressive indeed. But there was an excitement about the Dolphins that seemed to negate anything the 49ers had accomplished.

San Francisco Coach Bill Walsh, who had spent three years reconstructing his Super Bowl XVI championship team, was not about to blow this opportunity, though. This had become a deeper, more experienced, more versatile team, and it was especially strong in two areas that Walsh deemed critical-running game and pass rush. And the 49er secondary, mostly a bunch of raw rookies in 1981, had matured into perhaps the league's best.

This wonderful 49er balance proved too much for Miami, which depended heavily on Marino not only to generate points, but also to take pressure off a defense that had struggled for much of the season.

This time, Marino couldn't save himself, much less his teammates. San Francisco turned him into a mere mortal, and a harried mortal at that. And each time that Marino was sacked or another one of his passes was batted away, it became all the more clear that another Super Bowl title would elude the Dolphins, who had been denied an NFL crown two years before by the Washington Redskins.

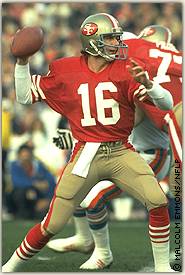

Montana, on the other hand, was outstanding and was named the game's Most Valuable Player, a distinction he had earned when the 49ers beat the Bengals in 1982. His 331 passing yards was a Super Bowl record, and his three touchdown passes were one off Terry Bradshaw's mark. But this multitalented athlete had another weapon, too. He was able to get outside the Dolphin pass rush, enabling him to pick up another 59 yards on the ground, which, of course, also was a record (for quarterbacks).

But every time the Dolphins tried to key on Montana, the 49ers would foul 'em up by turning to backs Wendell Tyler and Roger Craig. And they, in turn, shredded the Miami defense with their slashing runs and pass receptions.

Tyler, who had rushed for a club-record 1,262 yards in the regular season, gained 65 yards on 13 carries. Craig, a youngster from Nebraska, was even more effective, with 58 rushing yards, eight receptions for 82 yards and three touchdowns. In most years, that would have been an MVP performance.

The stunning ability of the 49ers to move the ball on the Dolphins -- they gained a Super Bowl-record 537 yards -- bore testimony to San Francisco's balanced attack, which was far more effective than the 49er offense had been three years before. In 1981, the 49ers could tease you with the run, but only the pass would kill you. In 1984, the run was an equally potent weapon, as the Dolphins were soon to find out.

About

the only dignitary who wasn't present at Stanford Stadium on January 20,

1985, was President Reagan, but he wasn't left out entirely. Reagan, via

television hookup in the White House, flipped the coin before the opening

kickoff. Former 49ers halfback Hugh McElhenny helped out on the field,

and San Francisco won the toss.

About

the only dignitary who wasn't present at Stanford Stadium on January 20,

1985, was President Reagan, but he wasn't left out entirely. Reagan, via

television hookup in the White House, flipped the coin before the opening

kickoff. Former 49ers halfback Hugh McElhenny helped out on the field,

and San Francisco won the toss.

Although runs by Tyler and Craig and first-down completions to Tyler and wide receiver Dwight Clark took the 49ers to the 41, they still had to punt. Miami took over at its 36-yard line, and Marino needed only six plays, starting with an opening-down 25-yard pass to running back Tony Nathan, to put the Dolphins in position to score. Even though a third-down completion to wide receiver Mark Clayton was two yards short of a first down, it set up a 37-yard field goal by Uwe von Schamann with 7:24 left in the first quarter.

Marino had made his team's first drive look so easy that even when Montana came back immediately to produce a touchdown and a 7-3 lead with 3:12 left in the period, Dolphins fans were not worried.

They should have been.

During San Francisco's eight-play, 78-yard march, Walsh revealed the basic elements of his well-conceived game plan. The 49ers wanted to take advantage of the Dolphins' linebackers, especially rookie Jay Brophy and second-year man Mark Brown on the inside, and they wanted to capitalize on what they saw as a blocking mismatch on the left side of the line, where 295-pound tackle Bubba Paris was facing 255-pound end Kim Bokamper.

San Francisco throws to its backs often, so it was important that the backs be able to beat the linebackers on pass coverage and continually chip away for short yardage. "We didn't intentionally set out believing that we wouldn't win without beating their linebackers," said Paul Hackett, the club's quarterbacks-receivers coach, "but it obviously worked so well for us that we kept using it until we could see if they would adjust."

On the first play of this second San Francisco possession, Montana flipped a pass behind the line to Craig, who gained six yards on coverage by outside linebacker Charles Bowser. Tyler then ran six yards for a first down. Two plays later, Tyler ran behind Paris and left guard John Ayers for six more yards and another first down at the 49er 49. After two more plays netted just three yards, Montana rolled out to his right, cut back left and scrambled 15 yards to the Miami 33, where Brown finally forced him out of bounds. This well-executed mix of plays set up the 49ers' first touchdown on the next play.

Montana rolled to his right and found

reserve running back Carl Monroe free down the right sideline. His beautifully

thrown pass went over Brown's head and past safety Lyle Blackwood into

Monroe's arms at the 15. Monroe slipped away from Blackwood and cornerback

Don McNeal and scampered into the end zone easily. Ray Wersching kicked

the extra point for a 7-3 San Francisco lead.

After Marino answered with a touchdown pass of his own, this one a two-yarder to tight end Dan Johnson, it appeared that the game was shaping up as the scoring free-for-all everyone had envisioned. Three of the game's first four possessions had produced scores, and with 45 seconds to play in the first quarter, Miami was on top, 10-7. Let's see, that adds up to about 68 total points at that pace.

Marino and Shula had crossed up the 49ers by running the series of plays leading to the touchdown with hardly a huddle. The tactic was not unexpected -- there had been reports all week that Miami would do it -- but the ploy still worked.

The 49ers like to shuffle players in and out according to the circumstances of each down, but the Dolphins' hurry-up tactics kept defensive coordinator George Seifert from making frequent replacements. That meant pass-rushing specialists Fred Dean and Gary (Big Hands) Johnson had to stay on the bench much of that time, taking pressure off Marino.

Marino certainly seemed unstoppable. After Nathan went up the middle for five yards to his 35-yard line on the first play of the drive, Marino completed five straight passes, including 18-and 13-yard bullets to Clayton, an 11-yarder to wide receiver Mark Duper and a 21-yarder to Johnson, who was tackled by linebacker Dan Bunz at the 49er 2-yard line. Johnson caught Marino's next pass in the right half of the end zone to give Miami its last lead of the game.

Clayton and Duper, or the Marks Brothers, as they were commonly known, had been conducting a weeklong gab session across the bay with the 49er secondary, especially cornerback Ronnie Lott. At one point, Clayton exclaimed: "All I'm hearing about is Ronnie Lott, Ronnie Lott. He's not on a pedestal, you know. He takes chances, and he can be beat. We aren't bad, either."

They were matched, however, against the most aggressive secondary in the league, one that earned its many accolades, which included a trip for all four starting backs to the 1985 Pro Bowl in Honolulu. "We certainly are going to make sure they know we are there," said Lott, a tough hitter who finally had gotten over a bunch of injuries and was healthy for the first time since the opening game.

Shula had figured that if Miami's aerial threat could force the 49ers into using their nickel (five defensive back) alignment exclusively, he could generate a running game, just as the Dolphins had in a playoff game against a six-back Seattle formation. Instead, the 49ers soon found that their nickel defense had all the answers to neutralize both the runners and Marino.

Marino had been sacked only 13 times in the regular season and not once in the playoffs. Given enough time, he hardly seemed bothered by defensive sets that featured six and seven backs. But the 49ers' pass rush changed all that in the Super Bowl; Marino was dropped a career-high four times even though the 49ers blitzed on just a handful of occasions.

It was the defensive front four that wore down Miami's fine offensive line. Dean, one of the league's premier pass rushers, usually is a spot player for the 49ers, but he stayed in the game longer than usual as part of the nickel personnel package. He teamed with Johnson, his former San Diego teammate who had been acquired in a September trade, to torment Marino.

Going into the game, the 49ers had marked the need to harass Marino without blitzing as a key to their defensive success. Such a situation would allow them to drop more players into pass coverage. They never dreamed they'd be so effective.

"Sometimes I didn't throw the ball well, sometimes I didn't have time and sometimes guys didn't get open," a disgusted Marino said. "They played the best any team has played against us defensively. They took us out of our scheme, I think. We knew what we had to do -- we had to throw the ball against a four-man line -- and we didn't."

In short, Marino ran out of miracles. He frequently forced the ball, causing his passes to fall short or long of his receivers or in the arms of the 49ers, who intercepted two of his passes and batted away several more.

Even though the 49er cornerbacks often dropped eight yards off the line, this quick-strike Miami offense, which relies so heavily on its receivers to get open deep, was limited to only one completion of 30 yards and just three other catches of more than 20 yards.

"He didn't have time to look us off his receiver," Hicks said. "He was getting too much pressure from our line. If he tried to go to another receiver, he would have to unload it in a hurry. We just told the line that we'd cover just tight enough to give them extra time to get in on him. We didn't care if he completed anything short. We weren't going to get beat with short passes."

The game turned on a stretch starting early in the second period and ending three Miami possessions later. In that span of 11 minutes, 55 seconds, the Dolphins had no first downs and only one net yard of offense, and Marino completed just one of six passes. San Francisco, meanwhile, scored three touchdowns in that span as its offense, led by an almost-flawless Montana, steadily improved.

The success of the 49er offense did not come as a surprise. The Miami defense, directed by ex-San Francisco coordinator Chuck Studley, had been lacking all season.

"After looking at the films," McKittrick said, "we said, 'This is a Super Bowl defense?' It's unusual for a one-dimensional team to make it to the Super Bowl, but Miami was unusual."

It had been Studley's plan to let the 49ers peck away with short passes while protecting against the deeper pass. But that scheme played right into the hands of Walsh, who was perfectly happy to take those controlled throws and dominate the Dolphins with steady gains.

"Bill had his game plan in surprisingly early," Clark said. "We just had a lot of time to perfect it. Everything that was open on film was open in the game, especially out patterns and stuff underneath for the backs."

The

49ers began to mesh for good early in the second period after a 37-yard

punt by Reggie Roby was downed at the Miami 47-yard line. Montana scrambled

for 19 yards, then threw to Clark, his favorite target, for 16 yards to

the Miami 12. Two plays later, Craig ran a curl over the middle after it

had been cleared out by tight end Russ Francis, caught Montana's pass at

the 3 and skipped past Brophy into the end zone for an eight-yard touchdown,

giving San Francisco a 14-10 lead (with Wersching's kick).

The

49ers began to mesh for good early in the second period after a 37-yard

punt by Reggie Roby was downed at the Miami 47-yard line. Montana scrambled

for 19 yards, then threw to Clark, his favorite target, for 16 yards to

the Miami 12. Two plays later, Craig ran a curl over the middle after it

had been cleared out by tight end Russ Francis, caught Montana's pass at

the 3 and skipped past Brophy into the end zone for an eight-yard touchdown,

giving San Francisco a 14-10 lead (with Wersching's kick).

Roby again had to punt, and his 40-yard kick was returned 28 yards by Dana McLemore to the 49er 45. Tyler immediately tried the right side for nine yards, and Craig ran left for six. Montana then threw to a wide-open Francis for completions of 10 and 19 yards and a first down at the 11. Craig ran over right guard for five yards before Montana spotted a blitz, saw a hole inside and scrambled up the middle six yards for a touchdown. Wersching's third extra-point conversion extended San Francisco's lead to 21-10.

Miami answered with a third straight Roby punt, which McLemore returned to the 49er 48-yard line. Following a five-yard sack by end Doug Betters, Montana threw against a blitz for 20 yards to Craig, who eluded Brophy's tackle. Montana continued to display his scrambling skills, running seven yards around right end before Brown forced him out of bounds. The officials ruled that wide receiver Freddie Solomon dropped Montana's pass on the next play, but TV replays indicated that Solomon caught and then fumbled the ball, which the Dolphins recovered. Nevertheless, Tyler then broke around left end for nine yards and another first down. Two more plays gave the 49ers a first and goal at the 5. Tyler carried the ball for three yards, and Craig then plowed in behind Tyler from the 2 for a 28-10 advantage with 2:05 left.

That's how the half should have ended. But Marino suddenly regained his accuracy and unleashed a fine two-minute drill that included seven completions. A 30-yard pass to tight end Joe Rose put the ball at the 49er 12, where the drive stalled. Two incomplete passes and a one-yard loss on a completion to Nathan followed, bringing on von Schamann, who kicked a 31-yard field goal with 12 seconds on the clock.

Even after that 72-yard drive, Miami wasn't finished yet. On the ensuing kickoff, guard Guy McIntyre picked up a bouncing ball and obviously didn't want to run with it. "I knew better," he said. But a couple of teammates urged him to run, and he started upfield, which was a mistake. He quickly was blasted by Joe Carter and fumbled, with Jim Jensen recovering the ball for Miami at the 49er 12. With 4 seconds remaining, von Schamann nonchalantly converted another field goal, this one from 30 yards, to close the gap to 28-16 at the half.

Whatever inspiration that turn of events gave Miami was quickly doused on the first series of the third quarter, when Marino was sacked by end Dwaine Board for a nine-yard loss on third down. San Francisco responded with a 43-yard drive that set up a 27-yard Wersching field goal and gave the 49ers a 31-16 lead.

From then on, it became a matter of how many points San Francisco wanted to score. After Miami's next possession, on which two sacks of Marino put the Dolphins back on their original line of scrimmage and forced yet another Roby punt, the 49ers tallied for the last time. Starting at his own 30-yard line, Montana hit Tyler over the middle for a 40-yard gain and followed that with a 14-yarder to Francis. Three plays later, Montana threw a 16-yard TD pass to Craig. Wersching's extra point gave the 49ers their final margin of 38-16.

Interceptions thwarted the Dolphins' next two drives. Cornerback Eric Wright nabbed Marino's pass for Clayton at the 49er 1-yard line in the third quarter, and Williamson picked off a pass intended for Rose in the end zone in the final period. The latter interception immediately followed a break for Miami when McLemore fumbled a fair catch and Vince Heflin recovered for the Dolphins at the 49er 21.

San Francisco ate up the clock on its final two drives, and the game ended as Marino recovered his own fumbled snap on a last, futile drive to the end zone.

Montana and his largely unsung comrades had thoroughly embarrassed the media darling Dolphins.

"Joe will never say it, but it's understandable that with all the talk about Marino he would like to do well," said Clark, Montana's best friend. "The talk pushed him. I know I am prejudiced, but he is the best quarterback around today, no question."

Walsh went further. "He is clearly the best quarterback in football today and maybe the best in many years," he said. "He is Number 1 in leadership, assertiveness, and he has those quick feet."

Montana is merely the NFL career leader in completion and interception percentage and overall passing rating. But he had thrown five interceptions in the first two playoff games, a statistic that clearly had San Francisco coaches worried.

They needn't have been concerned. Montana wreaked havoc on the Dolphins with both his arm and his legs, rushing for 59 yards and completing 24 of 35 passes for 331 yards, three touchdowns and no interceptions. His feel for pressure and his ability to pick out receivers on the run left the Dolphins drained and frustrated.

"We knew we had to contain him, but we couldn't," McNeal said. "You'd look up and he would be running around. They dictated to us; we never could dictate to them."

The loss was especially bitter for Shula, who had mentioned frequently during the playoffs that all of his team's accomplishments during the regular season would be tarnished by a Super Bowl defeat. Of course, he never imagined a trouncing of this magnitude.

Even the game's lone controversial play -- and the one that appeared to damage Miami most -- was shrugged off by Shula. That was the second-quarter play when Solomon appeared to have caught a pass on the Dolphin 13 and then fumbled the ball after taking a step and being hit by Lyle Blackwood. Blackwood picked up the ball and was on his way to the end zone when a whistle blew and the pass was ruled incomplete. The 49ers scored five downs later.

"We were dominated to the point where one play didn't make much of a difference," Shula said.

His players realized that, too. "The 49ers drilled us," Betters said. "Nobody ever did what they did to us."

Walsh, who felt tremendous pressure to repeat in the years following Super Bowl XVI felt nothing but elation after winning his second NFL title.

"This is truly the greatest moment of my career," he said. "And this was the best game we ever played since I joined the 49ers."

And one other thing: "Maybe this will prove," he said, "the merits of playing with a two-dimensional offense rather than relying on a one-dimensional attack."

After the 49ers' brilliant performance

in Super Bowl XIX, who could argue?

| Super Bowl XIX: 49ers vs. Dolphins | |||||

| Stanford Stadium, Stanford, California | |||||

| Attendance: 84,059 | |||||

| MVP: Joe Montana | |||||

| Winning Coach: Bill Walsh | |||||

| Miami Dolphins | 10 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| San Francisco 49ers | 7 | 21 | 10 | 0 | 38 |

| Mia - FG von Schamann

37 (7:36)

SF - Monroe 33 pass from Montana (Wersching kick) (11:48) Mia - D. Johnson 2 pass from Marino (von Schamann kick) (14:15) SF - Craig 8 pass from Montana (Wersching kick) (3:26) SF - Montana 6 run (Wersching kick) (8:02) SF - Craig 2 run (Wersching kick) (12:55) Mia - FG von Schamann 31 (14:48) Mia - FG von Schamann 30 (15:00) SF - FG Wersching 27 (4:48) SF - Craig 16 pass from Montana (Wersching kick) (8:42) |

|||||