|

|

|

January 29, 1995 - Joe Robbie Stadium, Miami

San Francisco

49ers 49

San Diego

Chargers 26

A few days before Super Bowl XXIX, Steve Young sat in a suite at San Francisco's team hotel and explained why he was smiling. "This is fun now," he said. "I am having so much fun at it. Before, I was pressing so hard, trying to outdistance criticism and skepticism and everything else. It just got sickening. I just had to do things differently."

So Young, the 49ers' brilliant quarterback, decided to forget that he was being asked to replace Joe Montana and began playing for the good of Steve Young. "My secret to success," he explained, "is that I have shown up for work every day no matter what was going on. Because you have to go through it. I chose to stay (in San Francisco), I chose to play here, I chose to do a lot of things. It is fun to look back on that now, but it wasn't fun then."

Young had tried to distance himself from the bitterness he felt about the Montana problem, created by everything from Joe's obvious jealousy of anything Young achieved to the organization's decision during the spring of 1993 to return the starting job to Montana even after Young led the league in passing in 1992. Montana eventually chose to leave the team and was traded to Kansas City. But even without Joe in a 49ers uniform, Young felt uncomfortable and, in many ways, unwanted in San Francisco. That is, until he stopped fighting the ghost and concentrated on what he could control.

"I'm a control guy anyway," he said. "I like to be in charge. If linemen called the signals, I would probably be a lineman. And I realized I couldn't control a lot of stuff that was bothering me. So I accepted it and moved on."

Now Young was only a few days from a coronation of sorts. Until the 1994 season, despite a career in San Francisco filled with gaudy statistics -- he has led the league in passing from 1991-94 -- he had been criticized for never winning a truly important game. He especially was haunted by consecutive losses to Dallas in the NFC championship game. But things had changed dramatically for him. The 49ers had beaten the Cowboys in the conference title game two weeks earlier, and he knew if the 49ers could beat San Diego in Super Bowl XXIX, and do it convincingly, he would be viewed in a different football light.

The

49ers had done everything possible to help him over this final hurdle.

In the off-season, they had brought in some veteran free agents to strengthen

their defense, players such as Richard Dent (Chicago), Rickey Jackson (New

Orleans), Ken Norton (Dallas), Gary Plummer (San Diego) and Deion Sanders

(Atlanta). It had been the defense, much more than Young's offense, that

fell short of being championship-strong in the 1990s. But to pay everyone,

the 49ers asked a number of players to accept renegotiated contracts that

would free up the needed money. And then some of the free agents, like

Jackson and Sanders, had to take one-year salaries far below their actual

worth. "But I wanted a ring more than anything else," Jackson said. "After

being in the league so long, it was worth taking a pay cut." Sanders conducted

a tour of the league, talking with such clubs as New Orleans and Miami,

before turning down lucrative long-term contracts to sign with San Francisco.

The

49ers had done everything possible to help him over this final hurdle.

In the off-season, they had brought in some veteran free agents to strengthen

their defense, players such as Richard Dent (Chicago), Rickey Jackson (New

Orleans), Ken Norton (Dallas), Gary Plummer (San Diego) and Deion Sanders

(Atlanta). It had been the defense, much more than Young's offense, that

fell short of being championship-strong in the 1990s. But to pay everyone,

the 49ers asked a number of players to accept renegotiated contracts that

would free up the needed money. And then some of the free agents, like

Jackson and Sanders, had to take one-year salaries far below their actual

worth. "But I wanted a ring more than anything else," Jackson said. "After

being in the league so long, it was worth taking a pay cut." Sanders conducted

a tour of the league, talking with such clubs as New Orleans and Miami,

before turning down lucrative long-term contracts to sign with San Francisco.

"I figured the 49ers were the team I had to go to to win a Super Bowl, and that is what I wanted," Sanders said. Both the 49ers and Sanders knew he would demand much more than his 1994 salary of $1 million to play for San Francisco in 1995. "Deion will not lose any money, just remember that," Plummer said. "He'll get back in endorsements from the win what he lost in salary."

Some officials from other teams were angered by the 49ers' liberal use of the new free-agency rules, charging that they were trying to buy a title. But San Francisco didn't deny its intent. To overcome Dallas, it had to become a better team. And to do that quickly, going the free-agency route was the only logical approach. "We wanted to beat the Cowboys and win another Super Bowl," 49ers President Carmen Policy said. "It is the goal that drives this franchise. Anything less will be a disappointment."

There would be no disappointments. With Young playing brilliantly and the defense holding up adequately, the 49ers routed the outmanned Chargers, 49-26, in Miami's Joe Robbie Stadium for their record fifth Super Bowl crown. It was the 11th consecutive victory in the Super Bowl by NFC teams, by an average margin of 22 points. And like so many of the games over the previous decade, this one was lopsided and lacking in drama.

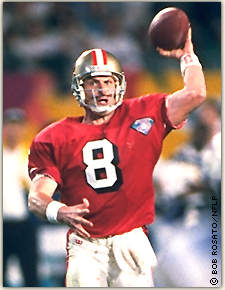

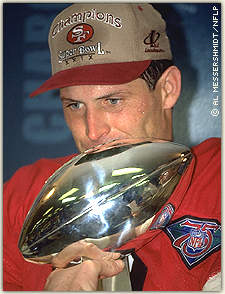

But

not for the relieved Young. He came through when he most needed to, going

24 of 36 for 325 yards and six touchdowns. He also was the game's leading

rusher, scrambling for 49 yards on five attempts. His touchdown total broke

Montana's record of five, set against Denver in Super Bowl XXIV, and his

passing yardage was the fourth-highest in Super Bowl history. He was named

Most Valuable Player, and he acknowledged this was his most important game-even

if Montana still has more rings (four).

But

not for the relieved Young. He came through when he most needed to, going

24 of 36 for 325 yards and six touchdowns. He also was the game's leading

rusher, scrambling for 49 yards on five attempts. His touchdown total broke

Montana's record of five, set against Denver in Super Bowl XXIV, and his

passing yardage was the fourth-highest in Super Bowl history. He was named

Most Valuable Player, and he acknowledged this was his most important game-even

if Montana still has more rings (four).

"All along, I felt I was playing against the past," Young said afterward. "Honestly, I have distanced myself from all (the Montana comparisons). I did so a couple of years ago. I want my performance to stand for myself and my teammates. It does a disservice to the team when it's talked about that way."

But even with Young's contribution, the whole Super Bowl event was a flop. The buildup to the game began with a whimper and got no louder. Of all 29 Super Bowls, this easily became the least anticipated, the least controversial, the least desired. The problem: No one could generate much hope that San Diego had any chance of winning. Even the Chargers, who talked bravely all week, never really sounded convinced they were better than San Francisco.

The anticipated matchup was Pittsburgh-Dallas or Pittsburgh-San Francisco. The Steelers built the best record in the AFC on the strength of an aggressive, blitzing defense that performed unlike any other in the league. At least the Steelers would have offered a different look for an AFC team after four years of seeing Buffalo's no-huddle offense crumble against superior NFC opponents.

But the Steelers messed up everything by failing to subdue the Chargers in the AFC championship game. Despite home-field advantage and a great passing day from quarterback Neil O'Donnell, Pittsburgh lost the lead, and ultimately the game, on a 43-yard Stan Humphries touchdown pass with less than six minutes to go. Then O'Donnell had a final-second pass attempt knocked down in the end zone to thwart Pittsburgh's dream. Suddenly, San Diego was in the Super Bowl despite leading in its two playoff games for less than six minutes overall. Of such things, long shots are made.

This was a franchise on an unexpected roll. General Manager Bobby Beathard, who constructed the Redskins' Super Bowl clubs of the 1980s, took over in San Diego in 1990, a year after quitting Washington. Two years into his regime, Beathard fired coach Dan Henning and hired Bobby Ross, who won a national title at Georgia Tech but was not considered an especially top-priority NFL coaching candidate. But Ross proved to be a tireless worker and organizer and, in Beathard's opinion, "the finest judge of talent of any coach I have been around," including Joe Gibbs, who was hired by Beathard to turn around the Redskins in the early 1980s.

The Chargers lost to San Francisco, 38-15, in December in a game that could have been considerably more lopsided. And San Francisco was on a huge tear, winning 12 of its last 13 games (including two playoff contests), and averaging more than 31 points a game over the season. The 49ers' 505 regular-season points were the fourth-highest in league history.

"In all my years in football, it is the most impressive offense I have seen," said Hank Stram, the coach of Kansas City's Super Bowl IV winner and a noted offensive innovator.

And, of course, the 49ers were coming off a 38-28 victory over Dallas in the NFC championship game, which many considered the "real" Super Bowl.

The result was a lopsided betting line. It started at 19 points, grew in some quarters to 20 or 21, then dropped to 18 as the game approached. But somewhere San Diego had to have some hope. So out trotted Joe Namath, he of "The Guarantee." Before Super Bowl III, Namath boldly predicted that his Jets of the American Football League would beat the heavily favored Colts of the National Football League. His Jets were 18-point underdogs when Namath spoke out.

"We're happy to be big underdogs," tight end Alfred Pupunu said. "There is no pressure on us. If we lose, we were supposed to lose. But if win, we shock the world."

Defensive end Leslie O'Neal was bold enough to say the Chargers "believe we can win. I wouldn't have come down here and wasted my time if I didn't feel like we can go out there and win this game. They have a good team, we have a good team. The bottom line is that we have to make plays to beat them. My biggest concern is that we go out and make a lot of mistakes and dig ourselves a hole that we can't get out of."

"I won't use the point spread as motivation," he said, "but the players are aware of what is going on. I'm not sure it is lack of respect, but you do have to wonder why people don't give us more credit for what we have done. We didn't come here just to play. We came here trying to win the game, knowing we are playing a great team."

That great team had to handle the pressures of expectations. Young, coach George Seifert, even Sanders, the Prime Time man, all had strong reasons to want to win this game. "If we don't win, we'll have to live with the disappointment and with all the questions about how we could have blown it," center Bart Oates said. "I don't think we will go into this game taking it too lightly. When you get this far, overlooking the Super Bowl would be ridiculous."

Oates was one of 15 present or former Pro Bowlers on the 49ers. This was a veteran, poised, extremely talented club that had taken on a new personality with the addition of the outlandish Sanders and rookie fullback William Floyd and the maturing of running back Ricky Watters. San Francisco always had reflected the cold, businesslike approach developed by Bill Walsh, who built the franchise into a Super Bowl-caliber club. But Sanders is in the business of entertaining, not just playing. "I want to give the fans their $200 worth," he said, referring to the price of Super Bowl tickets. That's why he is Prime Time. "I saw what running backs were making and what quarterbacks were making and I saw what cornerbacks were making and Prime Time was born," he said. "I had to do something to draw attention to myself."

As Sanders brought his flash and end-zone dance to the 49ers, Seifert slowly loosened his hold on player emotions. "This season has been more fun for everyone than I can remember," Seifert said. "I found Deion to be enjoyable. But this was a team that knew what it wanted to achieve and went about it in a good fashion. They had a goal in mind from the very beginning. With this team, nothing short of a Super Bowl was enough."

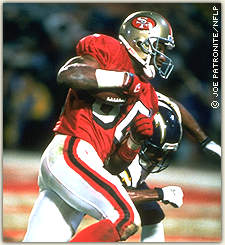

Not even Sanders did anything controversial leading up to the game. About the only unusual occurrence came early, when 49ers wide receiver Jerry Rice mentioned casually that he might retire before the '95 season. Rice explained he always considers retirement after every season, but talking about such a subject in front of 2,000 reporters tends to give it more importance. By the next day, Rice realized he'd better modify his statements. "I won't retire," he said, which put an end to the discussion.

Indeed,

Rice played against San Diego as if he could last another decade. Despite

a cold, and despite a slightly separated shoulder sustained in the second

quarter, Rice was his usual brilliant self. He caught 10 passes for 149

yards and three touchdowns. He now holds Super Bowl career records for

most yards (512), receptions (28) and touchdowns (seven). "Jerry Rice with

one arm is better than any receiver in the league with two arms," Young

said.

Indeed,

Rice played against San Diego as if he could last another decade. Despite

a cold, and despite a slightly separated shoulder sustained in the second

quarter, Rice was his usual brilliant self. He caught 10 passes for 149

yards and three touchdowns. He now holds Super Bowl career records for

most yards (512), receptions (28) and touchdowns (seven). "Jerry Rice with

one arm is better than any receiver in the league with two arms," Young

said.

Rice and Young quickly showed San Diego that this would not be a game where upsets were realized. To have any chance of winning, the Chargers had to prevent San Francisco from getting ahead early. Otherwise, they would not be able to control the ball with their running game. Their goal was to keep Young and Rice off the field, take time off the clock and hang close, hoping to benefit from turnovers. Instead, San Diego encountered its worst nightmare, first by losing the coin toss and having to kick off, then by having to stop the 49ers from striking quickly.

On

the game's third play, San Francisco sent Rice down the middle of the Chargers'

defense. Young said San Diego, which normally plays a two-deep zone, was

in a new defense, with four defensive backs spread in a line across the

width of the field. It was an alignment designed to prevent long passes,

but Rice still got behind the safeties and hauled in the 44-yard score.

Only 84 seconds had elapsed and San Francisco already was ahead, 7-0.

On

the game's third play, San Francisco sent Rice down the middle of the Chargers'

defense. Young said San Diego, which normally plays a two-deep zone, was

in a new defense, with four defensive backs spread in a line across the

width of the field. It was an alignment designed to prevent long passes,

but Rice still got behind the safeties and hauled in the 44-yard score.

Only 84 seconds had elapsed and San Francisco already was ahead, 7-0.

"On that particular play, a guy sneaks in, he broke through and he caught us by surprise," Chargers safety Stanley Richard said.

Then, after a quick San Diego punt, the 49ers were at it again. This time, they freed running back Watters down the middle. He was wide open when he caught a Young pass, then broke tackles from both safeties before finishing off the 51-yard strike with 10:05 left in the first quarter. This drive had required only 113 seconds and now San Francisco led, 14-0. No one had scored 14 points faster in Super Bowl history.

"It

wasn't coverages, it was miscommunication on the back end," San Diego cornerback

Darrien Gordon said of the second touchdown. Young faked a run to Floyd,

drawing in the linebackers, and the corners had to worry about Rice and

John Taylor running down the sidelines. That spread the field and opened

up things for Watters.

"It

wasn't coverages, it was miscommunication on the back end," San Diego cornerback

Darrien Gordon said of the second touchdown. Young faked a run to Floyd,

drawing in the linebackers, and the corners had to worry about Rice and

John Taylor running down the sidelines. That spread the field and opened

up things for Watters.

"The one thing we didn't want to do is fail behind early, and that is exactly what happened," Means said. Richard claimed "we knew exactly how good they were, but our problem was that we made so many mistakes, and when you make mistakes like that and give up big plays, you're definitely going to lose."

The Chargers tried to stay close. They put together an impressive 13-play, 78-yard drive, using the running of Means and a pass-interference cail against Sanders at the 1-yard line to set up a scoring dive by Means with 2:44 left in the opening quarter. Now, San Diego needed to make a big defensive stand on San Francisco's ensuing possession. Instead, the 49ers marched 70 yards on 10 plays, with Young hitting a five-yard swing pass to Floyd to finish off the drive. With 13:02 left in the half and the 49ers in front, 21-7, it was obvious San Diego wasn't going to win.

And

things only got worse for the Chargers. Dropped passes, stupid penalties

and an ineffective ground game -- Means, a 1,350-yard rusher in the regular

season, gained only 33 yards -- combined to render San Diego nearly passive.

An eight-yard pass to Watters late in the second period was followed by

third-quarter scores by Watters (on a nine-yard run) and Rice (on a 15-yard

pass from Young) to put San Francisco ahead, 42-10. The only suspense was

whether Young could break Montana's touchdown mark. His sixth score came

with 13:49 to play, on a seven-yard throw to -- that's right -- Rice.

And

things only got worse for the Chargers. Dropped passes, stupid penalties

and an ineffective ground game -- Means, a 1,350-yard rusher in the regular

season, gained only 33 yards -- combined to render San Diego nearly passive.

An eight-yard pass to Watters late in the second period was followed by

third-quarter scores by Watters (on a nine-yard run) and Rice (on a 15-yard

pass from Young) to put San Francisco ahead, 42-10. The only suspense was

whether Young could break Montana's touchdown mark. His sixth score came

with 13:49 to play, on a seven-yard throw to -- that's right -- Rice.

Arnsparger, the veteran coordinator, was stunned. "We were in man coverage, zone coverage, blitz coverage, but they beat us literaily in everything we did he said. ''There was nothing we could do on the sidelines."

Secondary coach Willie Shaw said it was like "leaving a slaughterhouse. We got out alive."

Ross said he thought his team was prepared. "We couldn't stop them," he said. "We didn't play things well in our secondary. Their efficiency and execution is something that is very special."

Seifert, who has been overshadowed by Walsh despite an impressive coaching record, called the victory "a wonderful job by the coaching staff and all the players. I don't know if it was that easy. San Diego did a wonderful job, but (the 49ers) just picked up the ball and ran with it."

Seifert's 49ers scored the most points (131) in postseason history, breaking the record (126) of Montana's 1989 49ers. Their least productive day came against Dallas, when they had to settle for 38 points. It was an efficient, effective, machine-like performance by a club far too talented for its AFC opponent.

For

Young, 33 years old, the moment was worth holding. "It was difficult to

face (Montana's challenge), and some days I wasn't sure I was doing very

good," he said. "You know the standards I had to live up to. That's why

this is one of the most precious times in life, to finally get there. Critics?

To hell with them. Go to someone else for a change."

For

Young, 33 years old, the moment was worth holding. "It was difficult to

face (Montana's challenge), and some days I wasn't sure I was doing very

good," he said. "You know the standards I had to live up to. That's why

this is one of the most precious times in life, to finally get there. Critics?

To hell with them. Go to someone else for a change."

Oates knew what he meant. "Steve made the comment on the sideline that he was going to take this monkey and pull it off his back," Oates said. "He said he'd had it on too long."

How many athletes really have ever adequately replaced a talent like Montana?

"It's the most difficult achievement in sports," said Mike Allman, the Seattle Seahawks' director of player personnel. "You don't just follow a legend and do well."

But for at least this one game, Young

didn't mind what player he had to follow. This was his moment and he was

relishing every second of it.

| Super Bowl XXIX: 49ers vs. Chargers | |||||

| Joe Robbie Stadium, Miami, Florida | |||||

| Attendance: 74,107 | |||||

| MVP: Steve Young | |||||

| Winning Coach: George Seifert | |||||

| San Diego Chargers | 7 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 26 |

| San Francisco 49ers | 14 | 14 | 14 | 7 | 49 |

| SF - Rice 44 pass

from S. Young (Brien kick) (1:24)

SF - Watters 51 pass from S. Young (Brien kick) (4:55) SD - Means 1 run (Carney kick) (12:16) SF - Floyd 5 pass from S. Young (Brien kick) (1:58) SF - Watters 8 pass from S. Young (Brien kick) (10:16) SD - FG Carney 31 (13:16) SF - Watters 9 run (Brien kick) (5:25) SF - Rice 15 pass from S. Young (Brien kick) (11:42) SD - Coleman 98 kickoff return (Seay pass from Humphries) (11:59) SF - Rice 7 pass from S. Young (Brien kick) (1:11) SD - Martin 30 pass from Humphries (Pupunu pass from Humphries) (12:35) |

|||||